In this age of instant gratification, intros are something of a lost art, which is why it’s heartening to see a song like “A Song for Harlequins”. Brought to us by a new prog-folk group called The Woolverstones (from England, as if you couldn’t tell from the name), “Harlequins” begins with an elegant duet between piano and flute. It’s never anything less than lovely, but there’s a sense of unease behind the sound, too; it sounds like an autumnal chill, just before twilight, when the wind begins to pick up and the leaves scrape across the ground.

I was immediately intrigued, and willing to hear whatever else the song had to offer. While it shifts gears from that intro, turning into a more straightforward folk song, it has a sense of purpose that other songs lack. It has a thrumming acoustic riff (reminiscent of “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, of all things), a well-rounded double bass line (shades of Danny Thompson) and a vocal performance that combines a rock star’s insouciance with a folkie’s understated charm. By the end, the flute comes back, and the song clatters to a halt as it hisses and trills.

It would have been nice if the song’s parts flowed together better; each part is very nice, but it doesn’t quite feel like an organic whole. But that’s a minor nitpick when you’re dealing with a band that has a sonic identity as well-defined as the Woolverstones. It’s an impressive achievement, particularly for such a young band, and I look forward to hearing more from them.

I had the opportunity to ask frontman Chris S. some questions.

You’re a fairly new band, having only formed towards the end of 2019. Has the experience of being in a band been as you’ve expected?

I would honestly say it exceeded our initial expectations. The camaraderie and bond is hard to beat. Bouncing ideas off each other and experimenting creates layers and new avenues — I feel like these new discoveries are more elusive when you are solo. Collectively, you have a shot at transcending the comfort zone. You are driving each other, in a healthy way, to take more risks. I feel like we are all more determined now than ever, to not fall back on old bad habits. Melodically, lyrically and structurally, I already feel a positive shift which is more refined than the music I was making before the band.

The three of you have been brought together by your shared love of folk music, particularly the progressive folk of the 60s and 70s. What are three progressive folk albums that anyone interested in the genre should listen to?

The Incredible String Band’s self-titled is seriously worth listening to. “Womankind” is one of the most sensual, beautiful songs imaginable. The vibe is utterly unique — seriously open and talented musicians, and with Joe Boyd as producer they were in great hands.

It’s highly debatable (and frankly inconsequential) whether Nick Drake falls into the progressive folk category, but I would urge anyone to check out all three of his albums: Five Leaves Left, Bryter Layter, and Pink Moon. Nick Drake was a one off. The intimacy he was able to create through his music. The way those albums were recorded are a miracle. You listen and you could swear the guy is sitting in the room playing live to you.

I want to throw in an album here (which definitely does not fall into the progressive folk category) which is a serious inspiration for our band: If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears by The Mamas and the Papas. This is pure musical serotonin. On dreary dark Northern European days, they bring you that golden Laurel Canyon light.

Your biography mentions the Woolverstones value “experimentation and improvisation”. What forms does that take, particularly in a genre like folk, which has traditionally been about songwriting and structure?

Adopting a playful attitude when it comes to structure, and not getting tied down to what’s traditionally expected, is important for us. As a band, our influences are highly eclectic and range from free jazz to blues, metal to classical composition. We are open to a diverse array of instrumentation–nothing is off the table. We’re also interested in experimenting in terms of how we record. For example, we would like to record a track at the back of our favourite restaurant in Rome whilst the dinner service is in full swing. Picking up on vibes is our highest priority.

You’re from the United Kingdom, and the song’s piano-and-flute intro is instantly evocative of a certain autumnal, pastoral English vibe. Is that purposeful? Was a statement intended?

It’s hard to say if it was consciously intended, but we are happy if it puts people in that place. The English countryside in autumn and winter does have a unique wistful quality, and that sense of melancholy was present in the process of devising the song. A sense of time passing and the bittersweet quality of life was somewhat of an obsession when we were composing — the flute is a delicate voice with an almost yearning tonality. There is a great mystery that seems to lurk in England’s church graveyards, meadows and fields — an enigma that is etched into our collective consciousness and certainly energizes us.

What’s the origin of the name “The Woolverstones”?

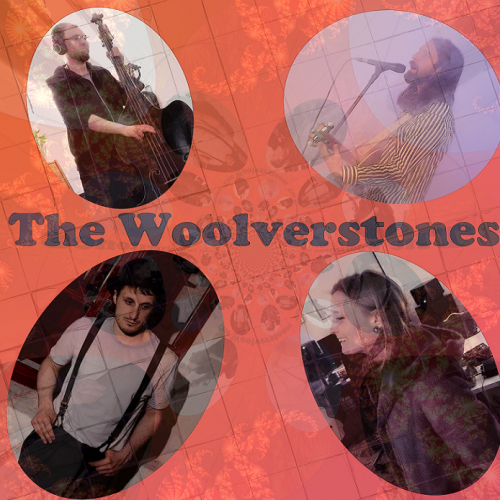

[Multi-instrumentalist band member] Jack Patching is from the small village of Woolverstone in England. One day [fellow band member] Louise [Tanworth] and I were riffing on some potential band names, and for some reason one of us uttered “The Woolverstones”. We both looked at each other and knew we had stumbled on something.

What does the future hold?

We have been booked to play at a Folk Festival in October (owing to the current health crisis this is uncertain at this point) and we intend to record our debut album in December. As soon as the current situation eases, the plan is to lock ourselves in a small house in the countryside for several weeks and work on new songs, practice, and hopefully create something unique. I like what Bob Dylan said when he did The Basement Tapes:

“That’s really the way to do a recording—in a peaceful, relaxed setting—in somebody’s basement. With the windows open … and a dog lying on the floor.”