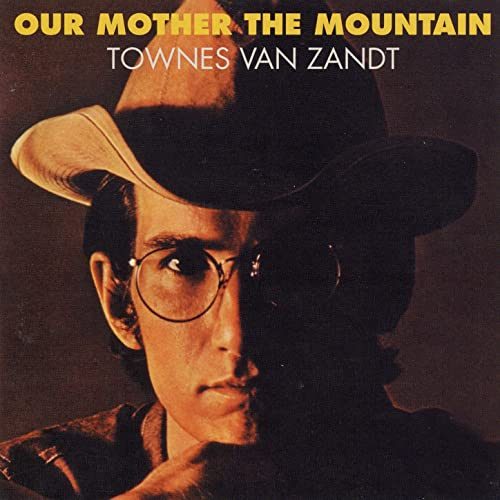

Most music fans – of any age – are likely not acquainted with the name or catalog of a man named Townes Van Zandt.

Almost every music fan, however, is likely familiar with the iconic musicians who cite Van Zandt, one of America’s all-time greatest singer-songwriters, as a major influence.

Outspoken admirers of Van Zandt include Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Robert Plant, Bright Eyes, Kings of Leon, The Avett Brothers, Frank Turner. The list is as long as a Texas summer day.

Among Van Zandt’s vast canon of remarkable work lies a terribly haunting, yet emotionless foretelling of love, death, and reunion. “Kathleen,” seemingly excavated from beneath all the layers of dirt, sorrow, hopelessness, and longing that weigh a humble man down, offers a glimpse into the mind of a man who’s finally, tiresomely arrived at his destiny.

Completely void of modern music’s “woe is me” emoting, “Kathleen” laments on his decision to, in the cool serenity of night, wade into the sea and kill himself in order to be reunited with his lost love. He offers no quarter. No mention of pity or plea, only snapshots that render the listener witness as the “stars hang high above the ocean’s roar” as “the moon has come to lead me to her door/there’s crystal across the sand/as the waves, they take my hand.”

“Soon I’m gonna see my sweet Kathleen”

Delivered over a simple arrangement of a single acoustic guitar and an ominous, foreboding string section that confidently announces the imminent, tragic verdict, “Kathleen” is as sparse yet sturdy as the shack outside of Nashville in which Van Zandt would live for many years.

After relocating from Texas, Townes will seek and eke out a home in a small, technologically-bypassed house with no electricity, running water, or plumbing. Save for the occasional trip to town to play a show (for usually fewer than 100 people,) Van Zandt lived in drug-induced reclusion.

The 1990s see him earning around $100,000 per year – 90% of that sum being royalty payments from higher profile artists such as Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris covering his songs. Nelson’s cover of “Pancho and Lefty” will ascend to number one on the U.S. and Canadian charts, speaking volumes of Van Zandt’s songwriting prowess.

Every penny, however, will be earmarked for the tools of his trade: heroin, codeine, alcohol, marijuana, and guitar strings.

His vices will eventually drag him to a depth that sees him offering all of the rights to his first 4 albums to his manager for $20.00. When he sings “maybe I’ll go insane/I’ve got to stop the pain,” he means it.

On New Year’s Day in 1997, Van Zandt will, after three decades of longing, finally be reunited with his sweet Kathleen, leaving an epitaph of masterful significance that will continue to lastingly impact the singer-songwriter genre for decades to come.