Change is the heart of Mon Rovîa’s “Don’t Lose a Good Thing.”

The song pleads, “Change with me, baby.” Mon Rovîa sings the line with as much intensity as any more standard love song plaint, like “Kiss me” or “Don’t leave.” There’s room for those, too, sometimes you do have to beg. But acknowledging that you are going to change, and asking someone else to change with you, is an uncommon, even an uncomfortable idea.

What if we change into people who aren’t in love?

A major cliché of romance is that two people can be essentially right for each other, and that love’s only challenge is finding the right person. The first verse of “Don’t Lose a Good Thing” alludes to this idea, worrying, “Will you find the right one?” But the song quickly complicates its story. Describing the addressee as “the closest to me,” Mon Rovîa sings, “Don’t lose a good thing.” This reminds us that love isn’t just a feeling, but an activity. People choose to be close.

This song could rest as a celebration of and request for closeness. But Mon Rovîa complicates it again. “Envision your smile when you open the door.” The first glimpse of the beloved is in the lover’s mind’s eye. They’re not immediately present: the first meeting is not in fact, but in imagination. By this, the idea of distance enters the song.

But rather than simply bemoaning distance, the singer says, “See how these miles have made us so close.” The space between lover and beloved connects rather than separating them. Because distance is something they’re looking across, facing each other, it becomes part of their relationship.

Measuring that distance becomes way of embracing.

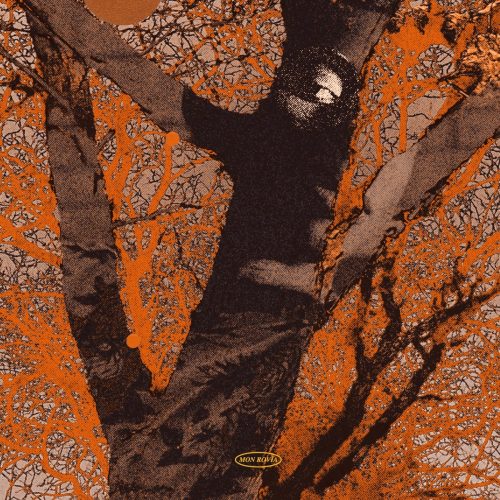

The song uses images of water to explore the paradox of distance that connects. The opening line, “Rain on the streets,” places us in a fluid landscape. The streets we move along are themselves moving, riverlike. Later we find the singer skipping stones – the water that divides him from the far shore also enables him to send a missive (pebble) across. Even the soundscape feels aqueous. Piano chords ripple and pool. Water is too slippery to mean just one thing. In this song, it is both separation and connection, the going and the coming back.

“Someday” and “always” are stock in trade for love songs, but Mon Rovîa uses them in a more complicated (a more loving) way than usual. “Nothing is always, but you found a way / so someday, I could come back to you.” Rather than saying that their love is forever and inevitable, the singer acknowledges that nothing – no feeling, no moment, no person – stays.

For these people to be together, they have to navigate change.

This line is the first we hear about the lover having left, but he must have, otherwise he couldn’t come back now. A future together isn’t certain for these lovers, much as the singer desires it. Maybe it’s this uncertainty that keeps stranding the singer “on the shores of silence.” Maybe – or maybe he’s just waiting for his beloved’s reply.