It’s January 19, 1971.

Contrasting the cold winter evening, Toronto’s Massey Hall is a radiator of heat, energy, and electricity. Omemee, Ontario’s (about 175 kilometers NE of Toronto) prodigal son, Neil Young, has returned for a much-anticipated, sold-out performance.

The stage is sparsely occupied, as his band Crazy Horse is nowhere to be seen. Despite having found substantial success with 1969’s Everybody Knows This is Nowhere (THE album arguably responsible for the entire Seattle ‘grunge’ movement,) tonight it’s just young Neil, an acoustic guitar, and a piano.

Near mid-set, the ever-introspective Young slows the concert into neutral and, in his trademark reserved, sagacious words, introduces a song that won’t find it’s way onto a record for another 18 months, cautioning:

“Ever since I left Canada about five years ago or so and moved down south, I found out a lot of things that I didn’t know when I left. Some of ’em are good, and some of ’em are bad. And I got to see a lot of great musicians who nobody ever got to see for one reason or another. But, strangely enough, the real good ones that you never got to see was ’cause of heroin. So I just wrote a little song.”

As the quiet, descending progression of “The Needle and the Damage Done” fills the room, nobody – aside from perhaps Young himself – could possibly make the connection between the descending D/Cadd9/Bb/F/E chords with the descent of one of Young’s closest friends and Crazy Horse bandmate Danny Whitten.

Young at once eulogizes those recently lost to, and currently battling the tidal wave, offering a poignant nod to Whitten, with:

I sing this song because I love the man

I know that some of you won’t understand

‘Love the man’ he did.

Following the success of Everybody Knows This is Nowhere, Young asks Crazy Horse back to the ranch to rehearse (and eventually record) 1970’s monumental After the Goldrush. Little did Young know, but his friend, guitarist, and in-house harmonizer has begun abusing heroin. Halfway through rehearsals for Goldrush, and due mostly to Whitten’s increasing unreliability, Crazy Horse will be dismissed.

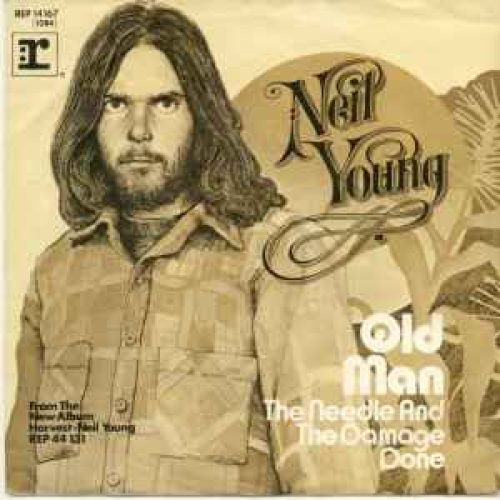

Almost 2 years later, and Young, in preparation for a substantial upcoming arena tour behind now-legendary album Harvest (on which “The Needle and the Damage Done” will first appear,) will beckon the members of Crazy Horse, Whitten included, back to Broken Arrow Ranch for rehearsals. One thing is immediately clear: Danny Whitten isn’t up to it. After frequent trips to the bathroom, lagging behind bandmates, confusion over progressions, etc., Young gifts Whitten $50 and a plane ticket to Los Angeles. He has pulled the trigger on releasing his friend and bandmate, setting in motion a series of events that will haunt Young for years to come.

On that fateful day in November of 1972, Whitten will return to L.A. and die that evening of an overdose, his sun finally relenting to an eternal, warm California night.