Some time in 1980, Stevie Nicks was talking to Jane Petty, the first wife of the late Tom Petty, about when she and Tom had met. Jane said they had met “at the age of seventeen,” but due to her thick Southern accent Nicks had misheard her. “No,” Jane corrected, “age.” But Nicks was undeterred; she was a songwriter, and she knew an evocative phrase when she heard one, objective reality be damned. “Jane, forget it. It’s got to be ‘edge.’”

Elsewhere in 1980, Nicks sat down in a Phoenix restaurant and opened the menu. Alongside whatever food they offered, there were facts about local wildlife. “The white wing dove sings a song that sounds like she’s singing ooh, ooh, ooh. She makes her home in the great Saguaro cactus that provides shelter and protection for her…” Another ingredient for some yet-unknown potion was stored away in her mind.

Then, in the last month of that same year, two things happened. Mark David Chapman shot John Lennon four times in the back outside of his residence at the Dakota, killing him. Nicks’ lover, record producer Jimmy Iovine, was a close personal friend of Lennon’s, and Nicks felt as though she could do nothing to comfort him. That was when the second thing happened. Nicks went to her uncle Jonathan’s house, to stay with him and his family as he died of cancer. She held his hand, along with her cousin, as he passed away.

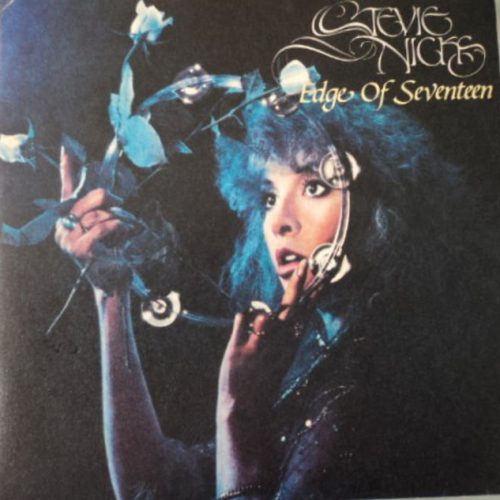

These elements may not seem like they would go together in one song at all, let alone in a song like “Edge of Seventeen.” Stevie Nicks has been stereotyped as a wispy, gentle fairy woman, but “Edge of Seventeen” is a hard-edged, arena-ready rocker. Its chugging, adrenaline-spiked guitar riff stands alongside riffs like “Eye of the Tiger” and “Lose Yourself” in its ability to pump you the fuck up. Destiny’s Child sampled it on “Bootylicious.” It plays in the background on American Horror Story: Coven, when a Nicks-obsessed witch sics a pair of alligators on some poachers. It does not sound like a song of grief; it sounds like a song of power.

Of course, in Nicks’ hands, it can be both. Just as her Fleetwood Mac material had an iron core of strength and resolve beneath the dreamy surface, “Edge of Seventeen” is as vulnerable a statement as “Gypsy” or “Landslide.” Like “Gypsy,” it’s a song that suggests a deep personal history, a past that colors the present: “He was no more than a baby then,” she reminisces, about meeting someone “all alone on the edge of seventeen.” It’s a powerful image, capturing a moment in time when you can taste adulthood and can sense the world opening up around you.

And like “Landslide,” it’s a song obsessed with the passage of time: what remains constant, and what fades away. “The days go by like a strand in the wind,” sings Nicks in the first line after the introductory chorus. Later, she reflects upon the permanence of the sea: “the sea changes color, but the sea does not change.” Throughout, she obliquely refers to her uncle’s death, touching on the decision to face this mortality, the music that played in the background, and the search for answers afterwards.

However, “Edge of Seventeen” is not a eulogy, and it is not a lament. You can listen to it a hundred times and not catch its meaning. This is because “Edge of Seventeen,” if you’ll pardon the technical jargon, kicks ungodly amounts of ass. Plenty of songs in the 80s sounded huge, but few sounded this urgent. Nicks’ trademark rasp is sharper than ever, and she delivers every line like she’s singing into the Grand Canyon. And there’s always some moment or delivery that leaps out and strikes you: the way Nicks barks out “the words of a poet and the/words of a choir”, the way she howls out the start of the bridge (“well I hear you! In the mor-ning!”), the way every repetition of the chorus barrels into you like a freight train.

The best part comes at the end of the third verse. The verse is of a different melody from the first two: more wild, more intense. It builds, and builds, as Nicks cries out about the rain and the sea and the passage of time, before finally reaching a boiling point: “at the eeeeedge ooooooof/Sev-eeeeeen-teeeeeeeeen!” Then, the riff snaps back into place, and Nicks unleashes a sound that starts as an “ooh” but quickly turns into a guttural roar: “ooh-oooooOOOOOOOOOAAAAAAAAAHHH!” It’s the kind of sound that comes from the heart and ends up ripping out someone else’s.

“Edge of Seventeen” may be a song borne from grief and sorrow, but it sounds unstoppable. It’s the sound of something thriving in inhospitable conditions, just like the white winged dove living in the arid desert. In this way, Nicks managed to provide comfort to herself, to Iovine, and to anyone else who needs to feel as though they can’t be hurt.