When you type “the jezebel spirit” into the YouTube search engine, without Brian Eno or David Byrne’s names attached to it, their song of the same name is only the sixth result. The previous five videos are from Christian sources, and they all patiently explain the concept of “the Jezebel spirit” without a hint of irony or metaphor. One video features a man with a Slavic accent drawing little cartoons to accompany his words – a demon’s face as he describes the “demonic spirit,” and what looks like ClipArt of a man and woman hugging as he describes “sexual urges.” Another features solemn piano music and an urgent male narrator warning us over stock footage of malevolent women and fire-lit faces. “The Jezebel spirit seeks control…the Devil seeks control through her.”

Which is to say that, even though it’s no longer the early 80s and televangelists are low-hanging fruit, “The Jezebel Spirit” still retains its relevance. As silly as the radio recording of an “exorcism” might sound, just as many people believe it today as they did when it was first recorded, along with the stigmatization of femininity and mental illness that comes with it. By taking that exorcism and putting a taut, twinkling Afrobeat groove under it, Eno and Byrne play with context, turning a hokey bit of religious burlesque into something fun, strange, and deeply sinister.

—

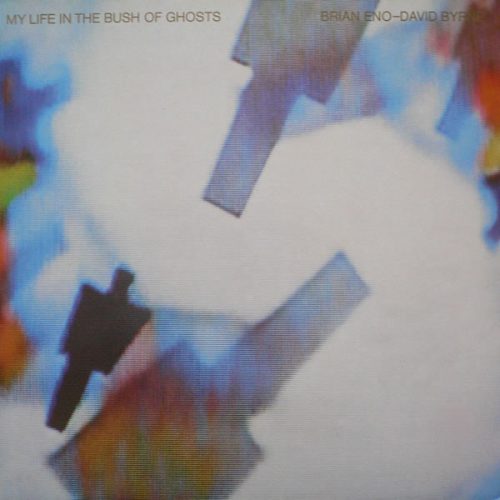

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, the parent album of “The Jezebel Spirit,” is a neat Venn diagram of its two creators. From Brian Eno, the art-rock auteur and electronic genius, we get typically brilliant production, with mile-thick grooves and voices processed into gibbering incoherence. From David Byrne, the eccentric frontman of Talking Heads, we get a preoccupation with the weird, loopy America found on road signs and AM radio stations, as well as a hint of playfulness that helps this paranoid record go down easier. (I’m willing to bet it was his idea to turn a pastor into James Brown on “Help Me Somebody.”) And in the middle, there’s a shared eclecticism, an experimental spirit in the truest sense of the word: two men throwing various elements together and seeing what happens.

Eno described My Life in the Bush of Ghosts as “visions of a psychedelic Africa,” and while there are plenty of polyrhythms and touches of high life guitar, it’s clear that the record’s real focus is on the other side of the Atlantic. “America Is Waiting” samples a liberal radio host named Ray Taliaferro, who passionately decries something or another over a tense, churning cauldron of clattering percussion and chicken-scratch guitars. (“No! Will! Whatsoever! No will whatso-ever!”) “Mea Culpa” takes a conversation between a nervous phone caller and a calm politician and turns them into two vultures chattering at the mouth of the abyss. There are moments of levity – “Help Me Somebody” features a passionate, Funkadelic-quoting preacher over a limber groove – but the dominant mood is one of alienation.

It’s not hard to see why. Recorded from 1979 to 1980, Bush of Ghosts is ripe with post-Watergate malaise: that sour, curdled moment in time when gas prices were astronomical, the religious right was on the rise, and it didn’t seem like you could trust anyone. It was becoming increasingly clear that Ronald Reagan would be the next president of the United States, and while no one could have seen the AIDS epidemic or Iran-Contra coming, it was clear that the devil’s bargain the Republican Party made with religious wingnuts was about to pay off in a big way. “The Jezebel Spirit,” then, felt like a preview of the frothing nonsense that was to come: these people were in charge now.

—

“The Jezebel Spirit” takes over a full minute to introduce the evangelist. First, Eno and Byrne establish the song’s groove, as well as its atmosphere of simmering tension. A single guitar note is picked over and over again, as incessant as a finger nervously tapping on a desk. A colorful soup of percussion bubbles in the background, clicks and pops and thumps, demonstrating both artists’ acuity for thistle-tight polyrhythms. (Bush of Ghosts was recorded before, but released after, Talking Heads’ Remain in Light, which used a similar sound to more accessible ends.) Occasionally, Eno throws in a queasy synth chord, just to remind you that the ground beneath your feet isn’t as stable as you think.

Then, with a decidedly sinister laugh, the evangelist begins to speak. “Do you hear voices?” he asks his subject. She doesn’t respond, or perhaps her response is edited out; either way, the evangelist continues. “You do? So you are possessed. You are a believer born again, and yet you hear voices and you are possessed.” He speaks with matter-of-fact authority, even though he just made a huge logical leap from “hearing voices” to “demonic possession.” With another diabolical laugh, he instructs his subject to “put [her] head there,” and sets to work.

Something curious about this evangelist (who has yet to be identified) is that he doesn’t sound like a stereotypical evangelist. He doesn’t speak with a Southern accent, instead affecting a clipped mid-Atlantic accent that makes him sound like a snobby professor from an old Hollywood movie. By the same token, he lacks the commanding presence or oily charisma of a Billy Graham or a Jimmy Swaggart. He sounds like a reedy little twerp trying to con people – which is most likely what he was. And yet millions of people fell for grifts that were only slightly less transparent, and continue to do so to this day.

Summoning every ounce of gravitas he can muster, the evangelist raises his voice. “Jezebel! Spirit of destruction! Spirit of greed! I bind you with chains of iron!” The music becomes less busy here, settling into a simple pulse to build tension. As his monologue continues, a chirpy, needly little synth sound plays, ratcheting the tension up even further. The subject, silent until now, begins to breathe heavily. The evangelist continues to try and drag the “demon” out of her, slipping into familiar misogynistic tropes. “Jezebel, you’re going to listen to me! She was intended by God to be a righteous woman! You have no right to her, her husband is the head of the household!” Finally, it builds to a climax – “Out, Jezebel! Out! In Jesus’ name!” – before exploding into a dizzily colorful rave-up. Eno adds a chiming synth figure that sounds like a malfunctioning carousel, the rhythms kick into high gear, and electronic treatments zap and zow and squeep all over the place. It’s exhilarating, but it also plays like a knowing punchline. What else did you expect? There never was a demon, anyway. There’s only a mentally ill woman being used by some creep with a radio show.

—

Purists might take issue with the fact that I’m writing an article about this song on a website devoted to the craft of songwriting. After all, neither Brian Eno nor David Byrne wrote a word of “The Jezebel Spirit”’s lyrics: they were listening to the right station at the right time, and came up with a great groove. But to me, songwriting isn’t just about writing words for music; songwriting can also involve taking pre-existing words and placing them in a fresh, intriguing new context that changes their meaning or brings subtext to the foreground.

After all, that’s how we engage with music, isn’t it? No song exists in a vacuum, and every listener brings their own life experiences to every song they listen to. When and where you hear a piece of music is often just as important to your interpretation as the music itself. It’s part of why I responded so well to My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and “The Jezebel Spirit” in particular.

I first listened to this album in December of 2016, a few weeks after Donald Trump won the election. The days were getting shorter, the weather was getting colder, and every headline made less sense than the one that came before it. The religious right were about to have their greatest victory since Reagan, and this time they were allied with a man of such inarticulate rage and petty cruelty that he made Reagan look like Mr. Rogers. We were standing on the precipice of a dark, miserable period in American history, and half the population was thrilled. Maybe I was naive to not see it coming, maybe I was rightfully shocked. In any case, what was once comforting and tangible no longer felt so secure. Everything shifted six centimeters to the right. Our country felt like another planet.

The album, as well as its centerpiece, served as a reminder that this had happened before. The world got uglier, terrible things happened, but it was noticed, it was recorded, and we moved past it for a little while. This music came from a time period very much like December of 2016, and it felt good to know there was precedent – followed by the queasy feeling that we had learned nothing.