Brian Eno is the kind of artist where people talk about his “importance” as much as they do his music. It’s understandable, even if it does Eno a disservice. His work with Roxy Music, as well as his early solo albums, shaped and warped glam rock at the same time, while also looking ahead to the sounds of post-punk. As a producer, he helped create some of the best and most influential records in rock history, including Talking Heads’ Remain in Light and David Bowie’s Berlin trilogy. And although Eno didn’t invent the concept of ambient music (which can be traced back to the 19th century), he was a pioneer of what modern listeners recognize as ambient: the genre in its current form may not have existed without him.

But more important than the significance of Eno’s music is the music itself. It wasn’t just that Eno made a post-punk song five years ahead of schedule: he made an amazing post-punk song five years ahead of schedule, as striking and intense as anything by Joy Division or Wire. It wasn’t just that he made some of the first modern ambient albums: those albums, such as Music for Airports and On Land, are still among the best ambient music you’ll ever hear. And it wasn’t just that he made glam rock: he made glam rock that sounded like the artful deconstruction of a genre that was still in its infancy.

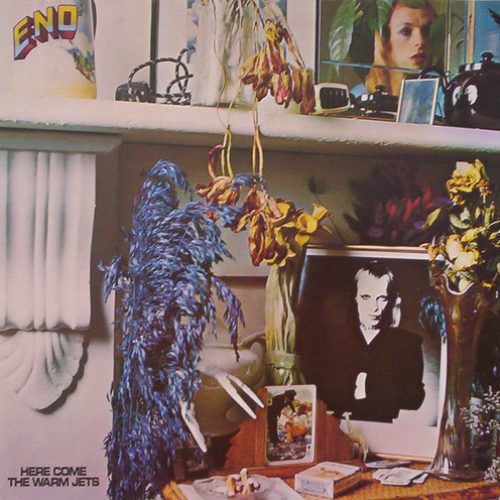

“Baby’s on Fire” comes from Eno’s solo debut, Here Come the Warm Jets. It was clear from his time in Roxy Music that he was a star: even though he sat away from center stage twiddling with synths and tapes, his avant-garde electronic treatments (not to mention his predilection for crossdressing) sometimes stole the show from peacocking frontman Bryan Ferry. But what makes Warm Jets and “Baby’s on Fire” so fascinating is that he doesn’t act like a star–the production is as much of a focal point as his vocals, and he cedes a large portion of the song to a guitar solo. But in the process, Eno proved himself to be something greater than a star.

You would never mistake “Baby’s on Fire” for a Roxy Music song. Even at their strangest (that is, at their most Eno-y), Ferry’s plummy, campy croon kept things from getting too unwelcoming. But “Baby’s on Fire” is tense, claustrophobic and sinister right from the start. Bass and synths pulse at just the right frequency to set you on edge, and guitars rev and buzz like chainsaws as Eno sings the main melody. It’s a catchy, pop-adjacent hook, but Eno doesn’t sing it that way. As he grew older (and sang less frequently), Eno’s voice would mature into a comforting baritone. Here, however, he sings in a pinched, snotty upper register, arch and campy but evincing genuine menace.

It’s the right performance for the song’s lyrics. “Baby’s on Fire” is about, well, just that: a baby, or a woman nicknamed Baby, being set ablaze. No song with that premise is likely to be overly cheerful, but “Baby’s on Fire” positively drips with misanthropy. Baby is too stupid to realize that she’s in any danger (“look at her laughing/like a heifer to the slaughter”), voyeuristic boys eagerly wait for photographs (“oh, the plot is so bewitching!”), and the photographers who come by to document the scene don’t even bother helping her (“take your time, she’s only burning/this kind of experience is necessary for her learning”). Even the narrator can only muster a half-hearted “better throw her in the water” before using Baby’s predicament as a macabre pick-up line (“they said you were hot stuff/and that’s what Baby’s been reduced to”). It’s a gleeful exploration of human cruelty.

As avant-garde as his music can be, Eno has always been keenly aware of his listeners: what effect certain music will have on them, what structures will work, and what they may want at a certain point in a song. He likely knew that sustaining “Baby’s on Fire”’s tension for five whole minutes would be torture for the audience. There would have to be some release, some exhilarating catharsis, something to pay off the song’s build-up while still feeling like an organic part of the song. Enter Robert Fripp.

The King Crimson guitarist has collaborated with Eno throughout their respective careers (that’s him playing guitar on David Bowie’s “‘Heroes’”, which Eno produced), but Fripp’s solo on “Baby’s on Fire” may be his finest hour. Although it functions like a normal guitar solo–it provides catharsis for the audience while displaying both Fripp and Eno’s virtuosity–it sounds like nothing you’ve ever heard. Other guitars have buzzed and wailed and snarled and shrieked, but they feel like the roars of tamed lions, making noise at the command of their trainer. Fripp’s solo here feels feral, something huge and dangerous coming much too close to you. You don’t feel safe listening to it, which makes it all the more jarring (and slyly humorous) how it sees itself out and lets the rest of the song continue as though it didn’t just rip the whole thing in two.

Eno didn’t make music like this forever. (Who could, really?) After Warm Jets and its follow-up, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), he began to pursue ambient textures in earnest. He released Discreet Music, his first full-length ambient piece, and his next “rock” album, Another Green World, was much calmer and more atmospheric: it felt like each song grew like moss on a rock in Eno’s garden. Another Green World is, of course, a stone cold masterpiece that paved the way for the rest of his illustrious career, but “Baby’s on Fire” is a reminder of just how thrilling Brian Eno’s music can be. He’s dedicated much of his career to making everything sound just right, but “Baby’s on Fire” shows us how good it can feel to be wicked, perverse, and wrong.