“I object to my government killing people because my government is meant to be me and I object to me killing people.”

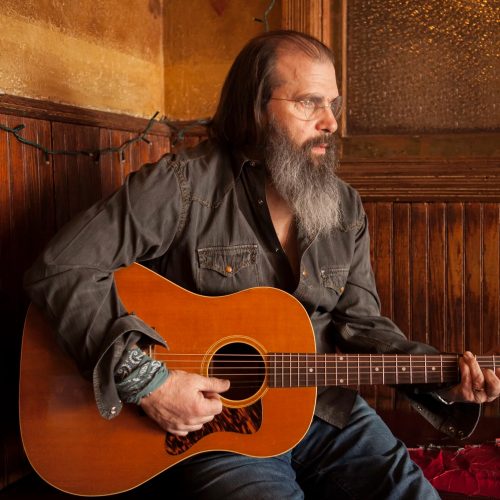

This is simply one of many damning quotes by legendary American folk artist Steve Earle regarding America’s arguably archaic capital punishment laws.

It’s 1995 and famed actor/producer/director Tim Robbins (The Shawshank Redemption, Jacob’s Ladder, etc.) is making the rounds, contacting his favorite musicians in the hope that they will contribute the soundtrack to his upcoming directorial project, Dead Man Walking.

After Springsteen and Johnny Cash climb aboard, offering works from the perspective of a death row inmate (Springsteen) and a more spiritual, religion-fuelled angle (Cash,) Steve Earle agrees and, as artists do, writes about what he knows – Texas.

I was fresh out of the service

It was back in ‘82

I raised some cain when I come back to townI went in to be all I could be

Come home without a clue

I married Dawn and had to settle down

So begins the regret-filled, haunted telling of Steve Earle’s “Ellis Unit One”.

Largely void of opinion, condemnation, pride, or any real emotional movement, the story instead quietly traces the thoughts and actions of a prison guard, tasked and paid to assist in the inhumane, menial activities surrounding some of the countless executions that would grow to follow him around, shackled to his psyche like an albatross tangled in a ball and chain.

O.B. Ellis (E1) is a behemoth, staggering Department of Corrections facility of 1100 hectares, and between 1965 and 1999, hosted every Texas execution. While states who uphold the death penalty have made some barbaric efforts to ‘humanize’ the procedure by introducing lethal injection, over 300 inmates were electrocuted between 1965 and 1977.

In some form of irony, twisted as the razorwire that garnishes the exterior walls, our prison guard – as heard through Earle’s voice – offers a glimmer of what will bloom into regret, reflecting:

I guess folks just got too civilized

Ol’ sparky’s gatherin’ dust

‘Cause no one wants to touch a smoking gunThey got that injection now and they don’t mind as much, I guess

They put ‘em down on Ellis Unit One

Perhaps most sobering is Earle’s nod to African American culture, legend, and enslavement. Like the slow-moving Rio Grande, Earle forms his chorus around the centuries-old song that encoded messages meaningless to those with the whips. Tired, defeated, Earle begs:

Swing low, swing low

Swing low and carry me home

Sung for decades by slaves in order to both communicate in an indecipherable manner, as well as pay homage to their ‘homeland’ (freedom,) a more fitting chorus one could not pen.

Many who served on the Supreme Court (the body through which capital punishment will be either upheld or abolished) have, from the safety of retirement, expressed both regret and disgust at decisions made during their careers.

Few have been more vocal about this than ret. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens. In a post-retirement interview with the New York Times, Stevens reached far to condemn the very institution responsible for the majority of his ‘successes’ in life, claiming the court “created a system of capital punishment that is shot through with racism, skewed toward conviction, infected with politics and tinged with hysteria.”

And therein lies but one of America’s societal failures – the unwillingness of a free, prosperous, educated man to use his voice when it counts. Literally.