Met·tle /ˈmedl/

Noun

A person’s ability to cope well with difficulties or to face a demanding situation in a spirited and resilient way.

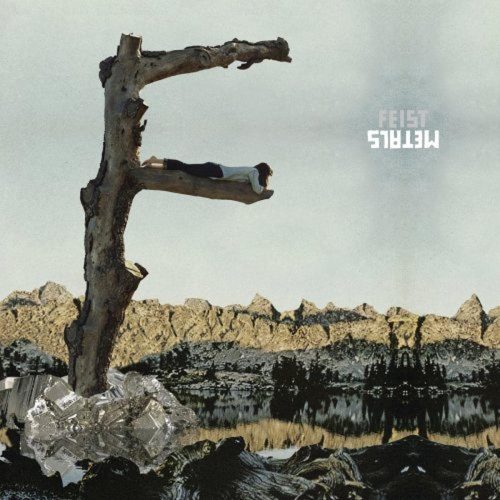

It’s early in 2011 and Feist, having just finished recording her fourth album, is happily considering the final strokes. In social and family circles, one of the most frequent questions she receives is “What are you gonna call it?” After realizing the pattern of reaction to her response (mostly hollow-eyed with a mix of frowns,) she opts for a more recognizable title. Mettle, as her experiences would dictate, holds no place in common vernacular.

Having recently read 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, Ms. Feist has extracted an interesting and often-overlooked observation of the conquest of the Americas: the way in which indigenous and European peoples utilized precious metals. While the Aztec and Maya found pride and identity in adorning themselves and their homes with gold and silver, conquistadors opted to forge blades and other tools of destruction with the metals that didn’t make their way east to the King.

Metals (Arts & Crafts/Cherrytree), much like the arrival of the conquistadors, begins with the percussive sound of what could easily be an approaching army meeting spear to shield. A few barres later the cyclical, anciently-modern opening guitar riff of “The Bad in Each Other” sets the album’s pace and tone as readily as an onslaught of pale-skinned, armored boatmen marching into the unexplored “New World.”

A stirring take on the “best-before” dates she notices among friends’ partnerships, “The Bad in Each Other” focuses a clear-eyed scope onto the worst type of relationship casualty – the devolution that occurs in the absence of a seismic event. The slow, lumbering decline of a partnership bottoming out well before either party is prepared to admit it seems as common as it is tragic.

Are we biologically programmed to wholeheartedly commit for only the length of time it takes to gestate, birth, and rear a child? Is our society rife with the narcissistic belief that thrill should trump depth of bond? Or do we simply grow in different directions, as cedars once caringly pruned, left unattended and free to explore any direction to which nature pulls them?

Routine, exposure, challenges, and lack of adventure are the oft-reported culprits that lead to the point where, as Feist proclaims in the chorus,

A good man and a good woman can’t find the good in each other

Then a good man and that good woman will bring out the worst in the other

The bad in each other.

Cue atonal, baritone mournful horns. Cue introspection of every “wrong” one has ever committed in a partnership. Cue the piercing simplicity of Feist’s ability to reduce a relationship psychologist’s profession to a chorus in an indie rock song.

Fast forward 11 years and several time zones from the Metals recording sessions. While on tour as the opening act for fellow Canadians Arcade Fire, she will awaken after the first stop in Dublin to very troubling headlines: Arcade Fire frontman Win Butler, decades known as a good man, is being accused of sexual misconduct resulting from a months-long Pitchfork investigation.

While convening with her bandmates at a Dublin pub, Feist realizes she has but two options: remain on the tour and indirectly communicate indifference or support for Butler, or exit the tour after only one show, potentially appearing as judge and jury.

After donating the proceeds from the first show’s merchandise sales to Women’s Aid Dublin, Feist will make the decision to “take responsibility and go home.”

In this brave and weighty move, Feist will finally seize the opportunity to release her mettle to the world.