“Florida Man.” Spring Breakers. Zola. Jason Mendoza shouting “Bortles!” as he chucks a Molotov cocktail at a boat. Miami Vice, Hotline Miami, Scarface. For decades, much has been made of sunny Florida’s seedy underbelly, to the point where the Florida of our public imagination is nothing but underbelly. The Sunshine State stereotype holds that the instant you step foot outside of Walt Disney World, you will be assaulted by some combination of alligators, Trump voters, and wild-eyed college sophomores with no fear of death. Yours truly is not immune to this, either: I admit that when I first heard about Tiger King, I assumed sight-unseen that it took place in Florida rather than Oklahoma.

The best art about Florida, like The Florida Project and Carl Hiaasen’s entire bibliography, recognizes that Florida is just one of fifty states, for better or worse. Beneath the wacky, colorful stereotypes, Florida is plagued by the same problems as the rest of America: climate change, income inequality, and the Republican sabotage of everything from public education to mental health counseling. But it’s also a place where millions of people wake up every morning, work, play, socialize, and live their lives. It’s not a lawless neon Thunderdome: it’s just a sometimes-beautiful, sometimes-ugly home, like every other state.

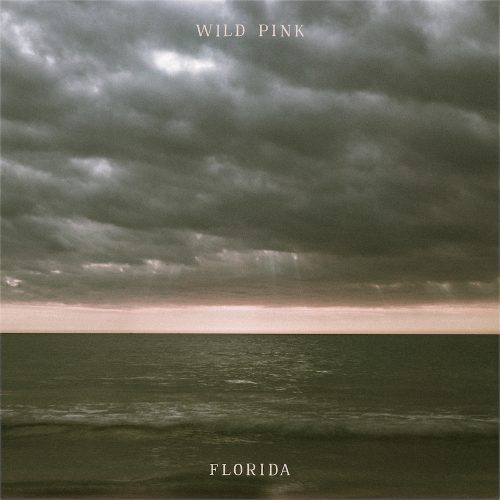

John Ross, the frontman of the dream-pop band Wild Pink, wrote “Florida” about his experience growing up in the Sunshine State. He says the state “has a bad reputation, which is well-deserved,” but he believes that it’s a “misunderstood state,” as well. As such, he plays with the perception of the state: he namedrops places like Tallahassee and Orlando, sure, and he mentions drinking blue margaritas at a Guy Fieri restaurant (an activity that is Florida-coded even if you’re not physically in Florida,) but he darkens and complicates the image as well. The cover art, featuring the ocean reflecting an ominous, stormy sky, says it all.

The narrator of “Florida” starts the song staring out at the ocean “with a troubled mind,” and we come to understand just why he’s so troubled. He feels disrespected, for reasons that may or may not have anything to do with his upbringing: “they talk about me like they know,” he sings, followed shortly thereafter by “they don’t know shit.” There are few things more frustrating than people thinking they know your life story because they know one or two things about you; luckily, his experiences with his significant other, drinking and singing and watching parades, reassure him.

The lyrics are solid, but the music is where “Florida” truly shines. It’s nine minutes long, but it earns that runtime: it moves and changes, subtly yet clearly, and the effect is like slowly panning a flashlight across a dark room. A churn of glassy saxophone textures begins the song, swirling in the distance like a coming storm, before it dissipates and gives way to an upright piano loop with a simple drum beat. Different elements fade in and out of the song: a saxophone lick, a hazy guitar strum, synth hums, and that’s all before the song is even halfway over. Like the home state it honors, “Florida” is dense, humid, more complicated than you’d expect, and uncommonly beautiful.