The trill is when a musician alternates rapidly between two adjacent notes. During the Baroque era, the trill was used as an ornament, a decorative flourish of just a few oscillations. During the romantic era, the trill had developed–quite literally, sometimes taking up entire measures–to deserve its former name of the shake as it could be used to devastating effect as composers elongated it. When you think of ‘shake,’ you think of tremors, both of earthly and nightly variety; you think of anxiety.

That is certainly what Franz Schubert used them for in his last few years of composing. Much has been made of the use of the trill in his last sonata, where it interrupts the chorale, pastoral melody as if a dark cloud has manifested: read Mark Swed’s “In Schubert’s last sonata, the trill’s the thing” for the LA Times or Alex Ross’ “The Trill of Doom” for The New Yorker for just a few accounts of the trill’s power in that composition. But tucked away at the end of the second movement of Schubert’s second piano trio is a trill that sounds just as ominous.

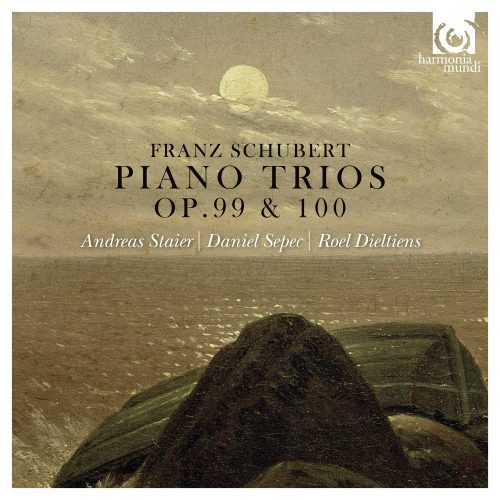

A little bit of context, here. Franz Schubert’s piano trios were composed in 1827, a year before his death at the young age of 31. The first piano trio feels like Schubert’s attempt to merge the playfulness of his famous ‘Trout’ quintet with the scope of the symphony. I’m not the first person to compare Schubert’s piano trios with the ‘Trout’ quintet, notable music historian Alfred Einstein – possibly related to Albert – has also compared both trios to it. Written at the same time as Winterreise, a 75-minute song cycle where colour gets sucked out into the cold, Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 1 feels like its opposite: colourful and warm. By contrast, his second piano trio offers more of that lyricism and intimacy, but adds in the existential dread and emotional weight of Winterreise and his last sonatas, exemplified by the second movement. Or, to defer to the other great Schu, Robert Schumann, the first piano trio is “passive, feminine, lyrical” while the second trio is “active, masculine, dramatic.”

If you listen to these works back-to-back, then the second movement always arrives as a surprise in its sobering funeral march. The piano strikes one chord per quarter beat, creating a march-like rhythm. The cello adds its rich and dark hum over top. Occasionally, the string comes in to provide contrast, only to be swallowed up by the darkness again. This culminates in the release near the end, and just as you think the movement is ending, the cello leads and deploys the fabled trill, and similar to its use in the last sonata, the trill is a shock. It feels like Schubert glimpsing death. And so, naturally, the second movement ends and we begin the dance of the Scherzo.

What else to do before we die, except try to live?