One could make a valid case for the 1990s being the last decade of true, unadulterated human experience.

A new yet unobtrusive invention called ‘the internet’ is, in its infancy, skirting the corners of society. Mobile phones won’t be a ‘must have’ until the turn of the next century, and most communication is conducted in the three dimensional, real world. The result? Humans bonding and binding across all facets of experience including art, education, awareness and appreciation of the present moment, oblivious to the swift and vast changes that lie in wait around the bend of time.

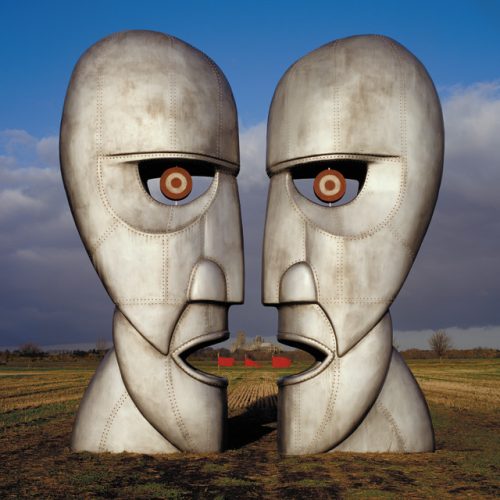

March 28, 1994. In a week, popular music’s anti-hero, Kurt Cobain, will be found dead above the greenhouse in his Seattle home. The ensuing upheaval will undeniably cast a long and static shadow over the new release of one of history’s most coveted, innovative, and commercially successful bands of all time: Pink Floyd.

The Division Bell, the band’s final record (and first without contribution from founding member Roger Waters,) serves as a stark, Nostrodamus-worthy warning of impending social shift. Isolation, the negative social impacts of digitized communication, dehumanization, and all of the next century’s perilous changes that will seep slowly and steadily in, unannounced and uninvited.

Nowhere on The Division Bell does the siren blare with more urgency than on the closing track, “Keep Talking.”

After seeing a television advertisement for British Telephone in which the digitized voice of Dr. Stephen Hawking warns of the aforementioned impending social doom (juxtaposed with hints of optimism and potential avoidance,) guitarist/vocalist/lyricist David Gilmour has been reduced to tears. Famous for layering recorded conversations (among roadies and managers) within some of their most iconic works, “Keep Talking” opens with the same warning that Dr. Hawking delivers in the stirring BT advertisement, beckoning:

For millions of years, mankind lived just like the animals.

Then something happened which unleashed the power of our imagination.

We learned to talk.

Rarely autobiographical, one would be justified in assuming the lyrics address many of the social perils that young people will face in the dawn of the 21st century, tackling allusions to social anxiety, self-doubt, and the inability to communicate face-to-face. “Keep Talking” walks us directly into an anxiety attack and the internal dialogue that typically cocoons such paralyzing episodes, complete with the echoes of frustration from a third party, clumsily trying to coax real, human communication out of a brick wall.

There’s a silence surrounding me

I can’t seem to think straight

I’ll sit in the corner

And no one can bother me

I think I should speak now (Why won’t you talk to me?)

I can’t seem to speak now (You never talk to me)

My words won’t come out right (What are you thinking?)

I feel like I’m drowning (What are you feeling?)

I’m feeling weak now (Why won’t you talk to me?)

But I can’t show my weakness (You never talk to me)

I sometimes wonder (What are you thinking?)

Where do we go from here (What are you feeling?)

Ironically, the only words of assurance come from the only performer who is actually incapable of speech – Dr. Hawking himself. As the pleading recedes momentarily, his emotionless yet confident words profess:

It doesn’t have to be like this

All we have to do is make sure we keep talking

Whatever was responsible for the cognitive ‘big bang,’ be it a random genetic mutation, the mastering of agriculture (which afforded early humans more free time, increasing the opportunities for abstract thought,) the ‘stoned ape theory,’ which posits that our unprecedented cognitive leap resulted from lower hominids ingesting natural hallucinogens, or otherworldly intervention, one thing remains certain: we have been gifted the ability to communicate in a manner unparalleled in the animal kingdom. Be it feelings, experiences, or knowledge, the gift is ours to maintain.

All we have to do is keep talking.