The ol’ in-laws.

Typically tolerated rather than cherished, “put your best face on and get through the dinner, already” kind of fodder.

If you’re English singer-songwriter Nick Lowe, however, this trope could not be farther from the truth.

Not when your (ex) father-in-law is The Man in Black – Johnny Cash.

It’s 1994 and Lowe, known for hits such as “Cruel to be Kind” and Elvis Costello’s “(What’s so Funny About) Peace, Love, and Understanding?”, has divorced his longtime wife Carlene Carter, step-daughter of Cash. Still, Lowe and Cash remain close, and Lowe invites Cash over to hear a scratch recording of a song Lowe has recently written.

Lowe watches, stretched across tenterhooks while “The Man” listens intently and introspectively to the recording.

“I like it,” remarks Cash, “but there’s only one problem – the first verse says everything. It’s perfect. I don’t possibly know what could follow.” He’s right.

The beast in me

Is caged by frail and fragile bars

Restless by day

And by night, rants and rages at the starsGod help the beast in me

Unbeknownst to Cash, Lowe has written the song with a selfless ulterior motive: he wants Cash to record and release it.

Cash does just that, and “The Beast in Me” is released on Cash’s collection of cover songs titled American Recordings, on April 26, 1994, 3 weeks after the passing of Kurt Cobain.

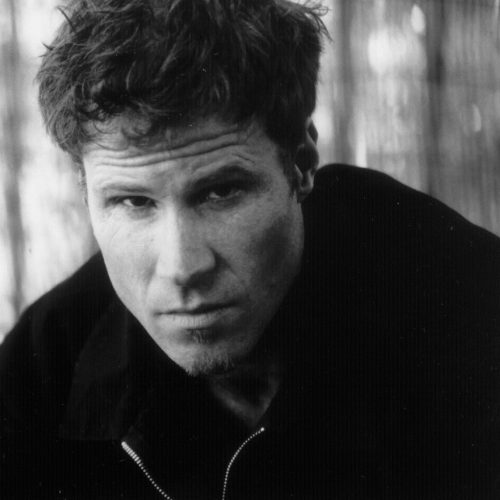

Fast forward 17 years and many albums, tours, deaths, and addictions, and Mark Lanegan (Screaming Trees, Queens of the Stone Age, Cobain’s best friend) has been asked to contribute a song to The Hangover II soundtrack. He uncharacteristically agrees, and offers a single option – his cover of Cash’s cover.

In his trademark Waits-meets-Cash timbre, Lanegan’s spatial, sparse, heart-slowing rendition cuts sharp and deep. Without knowing a thing about him (read Sing Backwards and Weep), it’s clear that, although he’s singing someone else’s words, these words exit his rusted core with the bleak hopelessness of someone who invented the English language and introspection in a single day.

“The Beast in Me” is nailed in place by one premise: awareness of one’s destructive behavioral tendencies. Neither apologetic or self-serving, it sits more like a silent prayer, a quiet moment of reflection intended for nobody outside of the singer’s own twisted, regret-filled mind, as Lanegan laments:

The beast in me has had to learn to live with pain…

And in the twinkling of an eye might have to be restrainedGod help the beast in me

Lanegan’s beasts could be first cousins with Cash’s. Both were lassoed and dragged through life by addiction, ruined relationships, uncontrollable tempers, and roller coaster highs and lows within the music industry.

Lanegan’s echoes of Cash (and Lowe’s) beasts could very well be the sound of his own being slowly, steadily, and dreadfully exorcised.