The first thing I regret about writing a Blaze Foley retrospective is that it is, by nature, retroactive—that is, that I am yet another in a long string of fans, reviewers, and artists who have come to know and appreciate his talent when it is far, far too late.

No amount of good things I say here will have changed that Foley lived nearly destitute and homeless in his life, nor that he was mostly forgotten outside of Austin after his untimely death.

So this review is selfish in its aim. It’s for you, the reader, to get the great joy of his music.

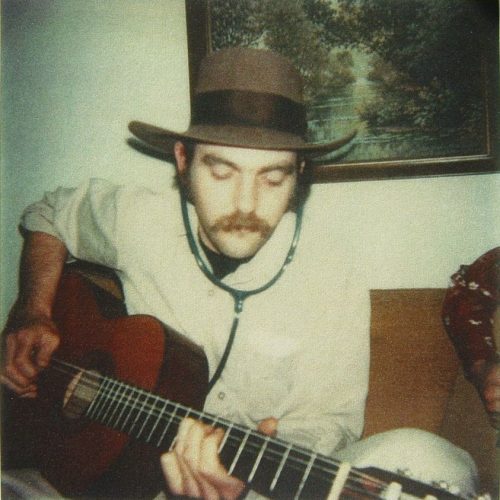

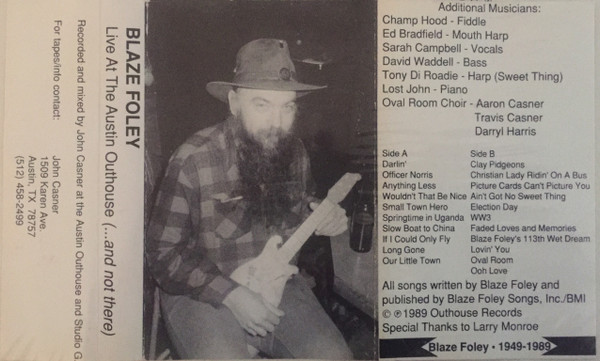

And what better way to enjoy than how it was originally heard—his voice and lone guitar in a local club, with the occasional back up of harmonica, fiddle, or piano? “Live at the Austin Outhouse,” Foley’s last recorded performance—and his last ever at his favorite club—circulated as a cassette around Austin for a decade after his passing in 1989 before it was finally released to the public. It was in December 1988, a little after Christmas, that Foley recorded this album over two nights, giving soulful live renditions of his classics, interspersed with his charmingly unpretentious adlibs in between.

Perhaps it only adds to his intrigue that much of Foley’s music has been lost in bizarre ways like this, hidden from the mainstream for a decade; another album was rediscovered by a friend of Foley’s years after his death—a vinyl he found in the back of his car—that was remastered and released, and there’s even reason to believe a missing album is in the FBI’s custody to this day.

Foley, notoriously rough around the edges, was also the kind of person who melted others’ hearts. That’s why he could couch-surf his way out of homelessness, that despite his antics people stood by and supported him. And this sweetness, on full display in the recording, is all the more heartbreaking and precious in the awareness that he would come to be murdered only a month later on February 1st, 1989, having confronted a friend’s son for stealing his father’s welfare checks—and being fatally shot.

But of course the album is not all premonition and grief. The intro song, “Oh Darlin’,” is classic ol’ trottin blues, a little lighthearted in his yearning for a loved one too far away. The closing lyrics are almost like an invocation for the beginning of the set:

Oh darlin’, oh darlin’

Way over yonder and I’m alone

Oh darlin’, oh darlin’

Come and hear my song, come and hear my song

The song that follows is bar none Foley’s most well-known—although, as is often the case for Foley, because a bigger country star lovingly covered it—and it covers an oft-discussed theme in his work: buses. Yes, there are two bus-titled songs in one album, and even more so Foley often covers the idea of transport or distance, just like “Oh Darlin” before. Spending much of his life wandering, catching buses between Georgia, Austin, and Chicago, Blaze emphasizes here a sense of hopefulness of what finally crossing the distance could mean:

I’m going down to the greyhound station

Gonna get a ticket to ride

Gonna find that lady with two or three kids

And sit down by her side

And ride ’til the sun comes up and down around me, bout two or three times

Smoking cigarettes in the last seat

Trying to hard my sorrow from to people I meet

And get along with it all, go down where people say y’all

Sing a song with a friend, change the shape that I’m in

And get back in the game, and start playing again

Here, Foley’s other compelling talent, and a trademark of his musical sound, is his impeccable Travis picking, on full display here. The other bus song, “Christian Lady Talkin’ on a Bus” is more a somber character piece, but there are still a few more which explore this idea of distance and yearning. “New Slow Boat to China,” a new version of the classic, both hopes for a long time to travel together, and also asks the object of his interest to wait for him, even if it takes as long as that slow boat to China. There’s “Our Little Town,” about the grief of an ex-lover moving out of town, and then, of course, my favorite of Foley’s: “If I Could Only Fly,” a song about wishing he could soar into the arms of his far-away lover.

This video was actually posted by an old friend of Blaze’s, and the comment section is rife with remorseful listeners, depressed at the idea that Blaze had to sing to an inattentive crowd.

But that he had good enough friends, who would want him to sing at their wedding this beautiful, honest song, always occurred to me as desperately kind.

Even his lyrics seem to wryly apologize to his audience:

You know sometimes I write happy songs

But then sometimes little things went wrong

You know I wish they all could make you smile

I had actually commented then. Had said, isn’t it so unbelievably loving that they’re going on partying and letting their friend sing his sad songs? And randomly, months later, I received a reply from the video’s owner. He said that’s what it was like: that he had never seen someone really so adored as Blaze was, even though he was unruly and rude with a drink, and perhaps not the best wedding singer. He notoriously patched up his clothes and shoes with duct tape, enough to earn a scoff or scorn from most, and yet instead was lovingly called a duct tape messiah. Later, his coffin would be wrapped in the stuff.

In fact, there were a lot of things Foley did against the norm. Two songs on the album—”Officer Norris” & “Election Day”—are fittingly rebellious and tongue-in-cheek (“You read us our rights but you read them too fast / Officer Norris would you please kiss my ass”). And he almost teasingly announces “Small Town Hero,” a song where his humor and wit go desperately dark, by saying, it’s “the song that makes his [friend’s] next-door neighbor cry the most.”

High school, high school, college too

Church on Sunday, learn the Golden Rule

‘Cause the devil, he might get you before he gets through

He might get you before he gets through

Whether funny, loving, heartbreaking—at the heart of what makes Foley’s music so compelling, especially live, is his commitment to honesty as a musical philosophy. In my own mind, Foley is a saint of honesty above all just like any loveable cynic. Just as the original cynic Diogenes in 400 B.C. harangued Plato from his home (a wine vat on the street), Foley wrote many moralistic anti-authority tunes seemingly at odds with his lifestyle, as a drunk and rabble-rouser (often temporarily) banned from many clubs and literally sleeping underneath pool tables while the games continued on above him.

A friend and contemporary, musician Lucinda Williams, wrote her own ode to him with his same rude, but loving honesty, called, “Drunken Angel,” describing him as “a genius and a beautiful loser.” All the testimony of those closest to him is thus riddled with awe and condemnation: “Blaze Foley was really two people. There was the caring, loving altruist, and then there was the ornery, drinking poet. The former killed him, the latter always was killing him,” peer Casey Monahan said, while fellow musician Michael Elwood shared a similar sense of awe at his wildness, “Blaze is remembered by Austin’s poets, pickers, pundits and police officers alike as one of the finest songwriters ever to howl at the moon.”

I never seen a wishin’ well

That held what it’s supposed to hold, but who knows?

Maybe somewhere there might be

I saw daylight in your eyes

I saw daylight in your eyes

I’m reminded by yet another classic figure, Li Bai, a Chinese poet from the 700s who was known as one of the 8 Immortals of the Wine Cup. Beloved, admired, and required reading to this day in Chinese classrooms, Li Bai’s poetic philosophy focused on the transience of life, on the friends he missed across the country, of his weariness over war and government. His death is mythically attributed to the poet having been so drunk one night he tried to catch the moon’s light in the water’s reflection, and drowned. It is quintessentially foolish, but there’s a charm in his naivete that I also see in Blaze Foley—a kind of foolishness that becomes wise.

The last song, “Oooh Love,” is simplistic in its yearning as Foley stretches each word into a stanza, drowning into the blue eyes of a lover and relishing in the way she admires him back.

Blue eyes~ she’s said, pretty blue eyes

said I… had pretty… blue eyes

See- me again, she wants to

see me again / she’s such a pleasant surprise

The song ends on his voice, cut before applause—no more ambient noise from the listeners, the clinking drinks or scuffling feet. Not even another adlib, just silence, and an awareness that this is the last we’ll ever hear from Blaze Foley. When the cassettes of this recording were being produced, he decided to send some of the money to a local homeless shelter, but it never came to fruition: the proceeds ended up covering his own funeral, another of his best efforts belied by tragedy.

Blaze was a lover of things alive, and plead their cause with every word.

Townes Van Zandt

But “Live at the Austin Outhouse” is an invaluable reminder of what made such a somber, difficult life worth living. In it, there is wit, humor, longing, companionship, and the profoundest love. Across distance, rebellion, heartbreak, is that moment among others, listening to an artist bare their soul, where parts of us get inexplicably healed. So even though it’s selfish—even though Foley can no longer benefit from our awe—in retrospect, how dearly underutilized was his gift by us the audience, for our own joy.

Blaze Foley is a reminder to those of us striving that we are loved, valued, meaningful, and important for more than our supposed successes. Rather, our meaning lies in what we choose to share of our struggles and our hearts—no matter how imperfect.