“We loved each other with a premature love, marked by a fierceness that so often destroys adult lives.”

This is a statement likely to rouse popular affinity because its sentiment is widely relatable. Many of us, have at one point or another, been victim to love’s vampiric seduction and bear concealed scars that we relish fondly in the dim light of our private moments. The human tendency to seek and find love is essential to how we fashion our identities. It acts as the shaky foundation on which we build the fragile idea of self. The instinct to connect runs deep in our species, and the way that we successfully build relationships with others informs a lot of who we are and why.

But suppose I told you that the quote above belongs to Humbert Humbert, the predacious and reprehensible protagonist in Nabokov’s eyebrow-raising classic Lolita. In that case, your reaction might be, not surprisingly, less commiserative. This scandalous exemplar of late modernist literature is, after all, one in a short list of modern classics whose lurid content and racy premise belong in the collective cultural unconscious. You don’t need to have read the novel to know that its plotline details the improper love affair between a middle-aged English professor and his prepubescent ward. Nor do you need to be a heavy-handed moralist to understand the unsavory implications of that relationship. Even when it comes to love and the heart, some things are just plain wrong.

But even as the notion of inappropriate and illicit intergenerational romance makes us grimace in disapproval, especially when it involves a minor, Nabokov’s use of it as the vehicle with which to probe our fundamental desires is still remarkable. You don’t have to approve or sanction Humbert’s nefarious behavior to recognize that there’s something much more complex at work. As a skilled observer of the human condition, Nabokov is aware of our latent impulse to keep looking when everything around us tells us not to. It’s this curiosity, capable of pulling us out of our emotional comfort zone, that feeds our appetite for material that’s incompatible with any personal or collective moral standards. There’s a reason why sex, violence, shock, and horror sell as well as they do.

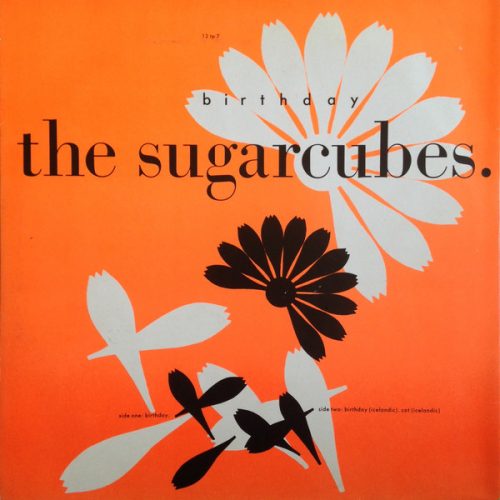

In this context, we can better grasp the book’s appeal and its beneath-the-surface subject matter. It’s also under this light that we can appreciate similarly provocative artistic statements. Enter “Birthday,” Icelandic band The Sugarcubes’ ground-breaking 1987 hit-single from their debut album Life’s Too Good.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=58bAgVSYV1E

A four-minute-long, upbeat ballad that features an eclectic range of parts including Einar Benediktsson’s equable trumpet; Sigtryggur Baldursson’s syncopated percussion; Bragi Olafsson’s warm and stolid bass work; Þór Eldon’s new-wave-influenced shrill tone; and Bjork’s clunky and rattling keyboards, this old-MTV favorite served as the Reykjavic-native’s introduction into the American consciousness.

Characterized by a fresh ‘80s-forward sound, the song quickly became famous for its odd and cryptic lyrical content about a five-year-old girl with some unusual habits:

She lives in this house over there

Has her world outside it

Scrabbles in the earth with her fingers and her mouth…

Threads worms on a string

Keeps spiders in her pocket

Collects fly wings in a jar

Scrubs horse flies

And pinches them on a line

That is a curious way to introduce a character that is, without a doubt, enigmatic. There isn’t much that we know about this girl other than “she’s five years old” and that whatever interests define her, they do not exist at home. Her life is spent outside, engaged in several strange and seemingly nonsensical hobbies. What’s interesting is Bjork’s decision to tell the story from a third-person perspective, making it feel as if she is looking out her window, able to see this child go on about her baffling business. It’s hard not to feel like she’s extending an invitation for us to come and observe with her, to watch this perplexing set of events as they unfold. And here, we come across that same “curiosity” principle. Curiosity, as we find out, doesn’t just keep us looking and listening. It also moves the plot along:

She has one friend, he lives next door

They’re listening to the weather

He knows how many freckles she’s got

She scratches his beard

She’s painting huge books

And glues them together

They saw a big raven

It glided down the sky

She touched it

By the third stanza, Bjork lets us know that the girl has a friend who lives in the house next door, which is not an uncommon thing for a child that age, particularly for one who spends most of her time playing outside.

What’s strange, though, is that this “friend” is an adult man. What’s disturbing is the degree of familiarity he has with the child, particularly with her body. The fact that he’s aware of specific details about her physical appearance, like the number of freckles on her face, suggests a closeness that’s hard to bear. This sudden revulsion is reinforced by how at ease the child feels with this man. She doesn’t perceive his interest in her as perverse. On the contrary, she sees him as someone whose presence and affection feed her interests and curiosity and allow her to discover the world around her. Her interest in all of these odd and eccentric activities, in a sense, mirrors a profound and fundamental interest in him.

It’s important to point out that at no point in the song do we get a clear explanation of what happens. Instead, Bjork concludes each stanza with a guttural cry that heightens the song’s emotional tension as it intensifies our desire for a resolution.

The song concludes with Bjork telling us that it’s the girl’s birthday, an occasion she celebrates with her adult playmate:

They’re smoking cigars

He’s got a chain of flowers

And sews a bird in her knickers

As if this tale couldn’t get any more objectionable, she concludes with:

They’re smoking cigars

They lie in the bathtub

A chain of flowers

Criticized and questioned when it first came out, the song’s intent isn’t different from Lolita’s, and it’s hard to argue the latter’s influence on the former. In a quote from Martin Aston’s biography on the singer, Bjorkgraphy, she explains that she set out to explore the way that not only “huge men, about 50 years old”, but also “material, a tree, anything,” can have a profoundly erotic effect on someone even when “nothing happens.”

In other words, nothing physical or concrete needs to happen for someone to be emotionally affected by a person or thing. Our mere interest in them, which Bjork and Nabokov contend are based on the innate desire in all of us to be both the object and subject of discovery, is enough to shape the way that we perceive our world. In coming to terms with the limits of what we’re allowed to experience, Bjork says, we can ultimately find the spiritual and emotional fulfillment we so anxiously crave.