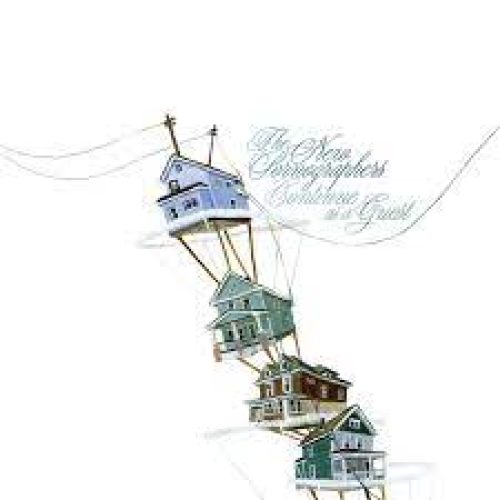

I rely on The New Pornographers for peculiar and beautiful songs, messages I can never decode but somehow understand anyway. “Pontius Pilate’s Home Movies,” from their ninth album, Continue as a Guest, is a mosaic.

A. C. Newman’s lyrics give us fragments of activity, fragments of landscape, occasional fragments of commentary (“beautiful, I guess.”) It feels there’s a lot going on: a journey on “the path through the mountains,” dangerous, so that you “sleep in your clothes now, it makes you feel safe.”

But it’s not a story you can summarize, only experience.

Some of the most vivid and concrete scenes of the song are entirely impossible. Consider: “On three, we burst through the Overton window.” It’s an action-movie break in. We have characters and dialogue: coconspirators whispering beyond the panes. We have a proper noun: maybe an Overton window is an Art Deco design, like a Tiffany lamp? It’s not: the Overton window is a term in political science that describes a spectrum of political opinions, from the unthinkable at one extreme, to the unthinkable at its opposite extreme, and in between, middle-ground positions of varying thinkability. This is not a window you can break with your foot. But it fits in a world where the morning has gracenotes, where “a home in the stars” can be found on a map. In this song, ideas can be touched, or kicked in.

What do you do with a song made of impossibilities and pieces of broken mirrors?

Before anything else, you groove. As you do, you discover a narrative arc in Joe Seiders’s drumming. This makes sense for a song that is (at least somewhat) about travel. The refrain “I got you a map to find a home in the stars / I hope you get there” tells us we’re on a journey; drums are the instrument by which to measure your steps. And if you’re wondering how to feel about everything that’s going on, the harmonizing saxophones will tell you: they are like town criers on the courtroom steps, solemn, resignedly mournful, delivering judgement. Needing a friend, you keep close beside Newman’s voice; needing a defender, you shelter behind Neko Case’s vocal force-field.

If, like me, you still want to squeeze some sense out of the words, take a clue from the title. The refrain, “Now you’re clearing the room, just like Pontius Pilate / when he showed all his home movies, / all of his friends yelling Pilate, too soon” stands out, partly because it repeats, but also because here’s our guy, Pilate from the title. We know him: fifth governor of the Roman province of Judea, who ordered the execution of Jesus. We also don’t know him at all. All that remains of Pontius Pilate the actual person is part of his name on a broken stone. What survives is Pontius Pilate, the character, as written by the authors of the Gospels, by Jewish historians of his own time, by later Roman historians, and by artists, playwrights, novelists, and screenwriters in all the centuries since. Their stories compose an enormous literary ghost.

Newman gives his version of Pilate a chance to self-narrate: anachronistically, he has a video camera, with which to make his own selection of scenes, from his point of view. But even his friends run out of the room rather than see things as he saw them. Pilate is a character in someone else’s story; at best, someone whose professional obligations left blood on his hands, at worst a villain. Who wants to see that from the inside?

Imagining what those movies might have shown, the fragmentary scenes in this song start to fit together. The sense of unintended disaster, ambiguous guilt, and political upheaval could all belong to Pilate. But they could as easily belong to Jesus, or to someone never made it through the mountains, whose story was forgotten. The line, “I got you a map to find a home in the stars / I hope you get there” could be spoken by any of these characters, to any of the others, but I think it’s Newman speaking to all of them. The story is the map, and home is what happens when we get to break out of the loneliness of solo experience. When we get to tell someone “This happened to me; listen, it was like this.”