Is Songtrust worth it? Short answer: probably. For the full story, read on.

If you’re an independent artist and/or songwriter with music on Spotify and Apple Music, then you’ve probably encountered this scenario:

You release your groundbreaking new single, and it gets enough streams to brag on Instagram about. You patiently await the fame and fortune that is your rightful portion, and you check your DistroKid (or CD Baby, Tunecore, etc.) account every day to watch the money pour in.

But as the months drag on, the money arrives in a trickle, not in a flood; by the time all the hype is over and your song plateaus at 60,000 streams, you’ve only received $19.46 in royalty payments. Not even enough for a Pizza Hut dinner box.

The music industry as a whole has been criticized in recent years for shorting artists and songwriters for the work that they do (especially streaming services). While there is a lot of validity in this (the industry changed forever alongside the technological revolution, and there is a ton of catching up to do), the complaints often come from a place of misunderstanding. The truth is that there is money being generated by streaming services, satellite radio, and other similar services. There’s just often nobody to claim it.

Independent artist-songwriters need to have a full understanding of every revenue stream in order to pinch enough pennies to make a living. There is a good deal of income that is A) due to independent artist-songwriters, but B) unavailable to them if they continue to work alone. That’s where Songtrust comes in.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. First, let me explain where the money comes from, and where it goes.

How Music Royalties Work

Compositions and Recordings

Since you’re doing this music thing solely for the immense wealth it will inevitably bring you (he said jokingly), you had better understand where the money comes from and where it goes.

When your music gets listened to or played – on a streaming service, during a TV or radio broadcast, at a live show, etc. – it’s earning you money. The amounts of money are called royalties, and different types of plays earn different types of royalties.

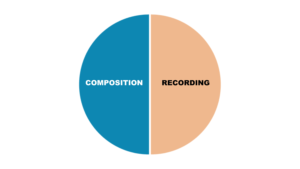

At the most basic level, the royalties earned from every song are split into two parts: those earned from the composition, and those earned from the master recording. Think of it this way, with the whole chart representing the total amount of money a song makes:

A composition is defined loosely by its original melody and/or lyrics. Think of it, basically, as the song itself, as an entity separate from any specific version or performance of it. When you write a song, you’re generating a copyrightable piece of intellectual property that only you (along with any other co-creators) have the right to use. Like any other thing you own, you are free to perform it, distribute it, sell it, and profit from it.

A recording is, essentially, the composition as the public hears it. When you record your song and release it (or if anybody else does), it takes on a tangible form which has its own copyright, separate from the melody and lyrics that you created; it’s a specific version of a song, defined by its unique waveform (I’m pretty sure neither of us wants me to get into how sound works in this article, so if you really want to know, go watch some YouTube videos like this one). Just like a composition, you (along with any other co-owners of the recording) are free to use a recording, distribute it, sell it, and profit from it.

So, when someone plays your song on Spotify (or anywhere else), it generates royalties for both of these things: the song itself, and the recording of it. Some of them are due to the writer (or owner of the composition) and some of them are due to the artist (or owner of the recording). If you’re an independent artist singing your own songs, then you’re owed both.

Simple, right? Bad news: it gets messier. Sorry in advance.

Types of Royalties

For every song, the composition half and the recording half are also split into two categories each: the composition half earns performance and mechanical royalties, and the recording half earns digital performance and master recording royalties. Think of it this way (though they’re not necessarily equal parts, as they appear in this chart, since their distribution depends on how your music is played):

On the recording side: Digital performance royalties are generated when your music is digitally streamed on any service that is not interactive – that is, listeners don’t choose the songs they hear – like Pandora or Sirius XM. In the US, they’re tracked, collected, and paid out by SoundExchange (this article isn’t about SoundExchange, but if you’re reading this and you’re not registered with SoundExchange, go do that; it’s free). Again, digital performance royalties are due to the owner of the master recording and the artist.

Also on the recording side: Master recording royalties are generated when your music is downloaded or streamed. They’re tracked, collected, and paid out by each individual streaming/download service and go to the distributor, whether that’s a label or an entity like DistroKid, CD Baby, or TuneCore (or an absurdly well-connected artist who found a way to put their music on streaming services without any help). The splits and final payouts are determined, then, by the distributor. (If you’re reading this, you probably already receive these royalties in full from your distributor.)

On the composition side: Mechanical royalties are generated any time a copy of your song is made and sold, like, for example, a CD pressing or a download. These numbers and revenues are reported and paid out by the distributor to the owner of the composition. However, the recent advent of streaming has complicated things, and it has been decided that streaming also generates mechanical royalties. In the US, streaming mechanical royalties are tracked, collected, and paid out by the Harry Fox Agency, a Mechanical Rights Organization (MRO). Here’s the problem many independent artist-songwriters face: these royalties are impossible to collect unless the composer is represented by a publishing company or a publishing administrator.

Performance royalties are generated any time your composition is performed live, broadcasted, or streamed, whether that’s in-person, online, on TV, or on satellite and terrestrial radio. They’re tracked, collected, and paid out by Performance Rights Organizations (PROs), and you have to be registered with one of them to be able to collect your royalties. In the US, the main three PROs are ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC, but similar organizations exist in other countries. But there’s one more wrinkle: performance royalties are split in half, with one part being owed to the writer and one part to the publisher. These are referred to as the “publisher’s share” and the “writer’s share,” and you can think of it like this:

If you are a songwriter, and you’re registered with a PRO, you are automatically paid the writer’s share of performance royalties. But, similar to the situation with mechanical royalties, many independent artist-songwriters don’t realize that in order to collect the publisher’s share of performance royalties, you have to either A) create a publishing entity and register it with every PRO (which would be tedious and take forever), B) join a publisher (which means the publisher has to want to sign you), or C) remain an independent composer (which means that you will miss out on the previously-mentioned mechanical royalties – since only publishers can collect those – and you can only register with one PRO).

Okay. Inhale. I know that was a lot of information. Exhale.

That’s everything you need to know about royalties, in a nutshell and explained with charts that may or may not have taken two minutes for me to make. Now let’s get to what Songtrust is and what it can do for you.

The Songtrust Model

To explain what Songtrust does, I’m going to highlight some key points from the previous section.

First, if you’re an unsigned artist singing your own original music, then you’re earning money from both the composition and the recording. The composition is earning you performance and mechanical royalties, and the recording is earning you digital performance and master recording royalties.

Second, having your music on streaming services like Spotify generates both mechanical and performance royalties. Any mechanical royalties generated from streaming are tracked, collected, and paid out by the Harry Fox Agency (in the US), but can only be collected by a publisher. Any performance royalties are tracked, collected, and paid out to your PRO which then pays you; but half of those royalties are designated as the publisher’s share, and can only be collected by a publisher or an independent composer.

Third, you can claim to be an independent composer to collect the publisher’s share of performance royalties if you don’t have a publisher, but in doing so, you will forfeit your right to collect mechanical royalties, because those are only accessible to a publisher. You are also forfeiting your right to collect outside of your home PRO (so you can’t collect overseas), because most PRO only allow exclusive membership (only publishers can be registered with more than one).

So, between mechanical royalties and performance royalties, independent artist-songwriters are almost definitely missing out on a significant amount of potential revenue, which is only accessible to a publisher.

That’s where Songtrust comes in.

Songtrust acts as a publishing administrator, which is basically a publishing company, but without expectations and quotas you have to meet, and you retain 100% of the rights to your compositions.

They are registered with all US PROs and all the major PROs from other countries, as well as with the Harry Fox Agency and all major MROs from other countries. Every time you register a song with Songtrust, they start digging in the US and around the world for any royalties that you are owed. Essentially, they can do all the dirty work of tracking, collecting, and paying out any overlooked or black-boxed royalties and getting them to the rights-owner. The important thing: this means that they are able to collect any money that is only payable to the publisher, which, in the world of streaming, is a decent percentage.

Is It Worth It?

Almost definitely. They’ve thought of pretty much everything and do all of it thoroughly. (I promise Two Story Melody is not affiliated with them at all. Yet.)

Songtrust’s pricing is relatively cheap ($100 one-time fee plus 15% commission for a lifetime membership) and they deliver money as fast as any traditional publisher. The commission fee is small compared to the 50% publisher’s share that you may be already missing out on. Their online tools are very intuitive, and they make other parts of the business easy: they can even affiliate you with a PRO right from their platform. They’re connected with 45+ collection agencies, and have extensive resources to tell you everything you need to know about tracking down all of your due royalties (to write this article, I did a lot of research, and pretty much every online source was either on their website or linked to their website).

They’ve got it all covered. Seriously. They thought of everything.

The only real reasons to not use Songtrust are A) you’re planning to be signed to a traditional publisher very soon or are already signed to one, or B) you’re absolutely certain you will never earn back the $100 fee. Reason A is legit, but traditional publishers have their pitfalls and there’s never a guarantee you’ll get a pub deal. Reason B is the same as not believing in yourself or your music, which you and I both know is not a good mindset.

So, if your songs are getting listens and you’re wondering why DistroKid has collected $0.46 for you (no shade at DistroKid; I use them, but even they suggest Songtrust), or if you think you’re owed money but all this talk of splits and percentages and shares was confusing (rightfully so), then Songtrust is perhaps the easiest way to make sure you’re getting the money you are entitled to as the groundbreaking songwriter and rights-owner you are.

Last note: here are some helpful sources if anything is still unclear.

How Spotify Streams Turn Into Royalties

DistroKid is Not Enough to Collect Your Performance Royalties

CD Baby vs. DistroKid: Music Distribution and Royalties