It’s been about a week since self-quarantining started, and I’m holding up as well as I could expect given the situation. I’m staying inside as much as possible, which isn’t anything new, but I’m also making time for daily walks to get fresh air. I’m finding ways to keep myself busy and entertained; I’ve been watching old movies on YouTube, and the backlog of books I’ve wanted to read is steadily being cleared. I’m disappointed that all the movies and festivals and sporting events have been cancelled or postponed, but for now I’m healthy, safe, and content.

I take in small doses of reality, which is about all I can manage. The coronavirus will essentially shut down American life for months. Millions of people will get sick, and hundreds of thousands will die. The federal government is hamstrung by the hopeless incompetence of its president, and while individual states may have competent leaders there are only so many hospital beds and ventilators. The economic fallout of the virus and the extended quarantine will be catastrophic; we will fall into a recession, perhaps even a depression. If I think about it for too long, I feel sick.

I’m the sort of person who takes comfort in Life Going On. I’m soothed by the fact that this won’t last forever, that one day the virus will go away and allow us to go back to something that resembles normalcy. But the ambient hum of fear is always there, and nothing can tune it out: maybe things will never go back to normal. Maybe you’ll be stuck at home for years on end. Maybe you’ll always hold your breath when you walk past a stranger. Maybe the foundation of your daily life was built on a sinkhole, and you’ll always be afraid that the ground will open up and swallow you again.

Quarantine, the breakout album by the incomparable Laurel Halo, came out in 2012; that was the year we thought the apocalypse might come before we came to realize just what the apocalypse felt like. Nowadays, just about any album with a vague sense of fatalism gets called “the soundtrack for the end times”, but Quarantine is the genuine article; not just for its pitch-perfect evocation of modern dread and alienation, but for recognizing that the end times aren’t actually the end of anything. Even as the world careens from one disaster to another, Quarantine suggests, with its dreamy, weary tone, that we won’t get the straightforward satisfaction of a metaphorical earth-shattering kaboom. It’ll just go on like this: people stuck in loops, going about their lives while the world feels less real every passing day.

Laurel Halo is one of the best electronic musicians of the past decade, and Quarantine is a brilliant showcase for her particular gifts. Halo has an unparalleled ear for evocative sounds, and she puts that skill to good use on Quarantine, where she uses colorful synth arpeggios and disembodied voices to create a cyberpunk dystopia as beautiful as it is nightmarish. It’s a world of glimmering neon, of billboards the size of skyscrapers, of pulse-pounding chases and fleeting human connection. Sonically, it owes a debt to Vangelis’ Blade Runner soundtrack, as well as IDM artists like Autechre, but it’s all filtered through Halo’s singularly warped perspective.

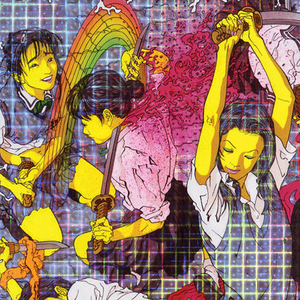

The cover of Quarantine sets the tone: over a sparkly gradient, stylized Japanese schoolgirls gleefully mutilate themselves with samurai swords, gushing magenta blood and candy-colored gore. It could come across as base provocation, but it’s so off-kilter that it’s hard to tell just what you’re looking at from the first glance. At any rate, it’s the perfect album cover for Quarantine: beauty and ugliness and peace and horror and surrealism, synthesized until it all feels like the same thing.

“Years”, for instance, features a beautiful lavender shimmer of an electric piano, sounding like a vague memory of happier times. It then proceeds to distort its beauty by adding a low, ominous synth hum beneath it, as well as Halo’s elliptical lyrics sung in a flat, unnervingly direct tone. Meanwhile, “Thaw” sounds like its title, starting with an eerie electronic warble before turning into a tentatively hopeful future-pop song. It’s one of the record’s more hopeful moments, but there’s still something uneasy and uncanny about it; it sounds like someone making pop music after centuries of no music at all.

“MK Ultra” has a graceful synth arpeggio instantly reminiscent of a futuristic city, but the song itself is cold, cryptic, and chilling. Halo gets a lot of mileage out of implication; the lyrics of “MK Ultra” say little directly, but it hints towards paranoia (“oh, what if you care?”), impending doom (“Hurricanes always coming/so take cover or run”) and necrophilia (“you’ll make love to cold bodies/fresh after they thaw”). Those details, coupled with the song’s name (a CIA program exploring the possibilities of mind control), paint an eerie picture that may be closer to reality than we’d like.

For a record more concerned with soundscapes than typical songcraft, Quarantine shows that Halo has a great eye for choosing just the right word to set things off-balance. Going back to “Years”, one of the three sentences Halo repeats over and over is “you’re mad ‘cuz I will not leave you alone”. It’s a wonderful lyric, precisely because it’s something no non-android would ever say. Not only is it a blunt, almost childish statement, but it’s an odd mix of informal (the use of the word “mad”, as well as “‘cuz” instead of “because”) and impersonal (“will not” as opposed to “won’t”). It’s almost subliminal in its uncanniness, but the effect is felt all the same.

Elsewhere, there’s “Carcass”, which takes Quarantine’s simmering unease and cranks it up to a full-blown panic attack. Over a palpitating bass and whirring synths, Halo’s digitally cracked voice cries out: “my carcass!” It’s another example of Halo’s great word choices: it’s not “my body”, or even “my corpse”, but “my carcass”, implying that her body is just another piece of meat to be butchered and re-purposed for someone else. It’s easily the album’s most fast-paced moment, and it reminds you just how dangerous the world of Quarantine (and by extension, our own world) really is.

At the end of this cold, eerie, abstract album comes “Light + Space”, a song of such genuine warmth and beauty that you almost wonder if you’re being tricked. The synthesizers glow and hum in oranges and purples like a digitized sunset, and the song’s floating, beatless majesty suggests a hard-earned peace. Is there a catch? Is this like the ending of Brazil, where the protagonist is so broken by the torture of a dystopian regime that he retreats into a fantasy? No. There’s no final rug pull; there’s only a bittersweet ending.

That’s what makes Quarantine so resonant in our current moment. The world is a frightening, lonely place, and it grows more frightening and more lonely by the day. You may feel paranoid, alienated, helpless, hopeless, and you may not be wrong. But there is grace and beauty and humanity to be found, even in the ugliest parts of modern life. There is the cool blue glow of a computer screen, the majesty of the city at night, the precious warmth of momentary human contact.

And, if you look hard enough, you may even find a way out; a way to get better, a way to fight back, a way to make the world even a fraction less cold and isolated. That’s the benefit of this slow apocalypse: if the world ends slowly, you can at least work to change course. We’ll never get a utopia, but maybe we don’t need one.

To help people in these trying times, consult articles like these to see how to make a difference in the fight against COVID-19.