About a month ago, I published what I thought was a pretty fair / detailed review of Playlist Push.

(If you haven’t heard of Playlist Push, it’s a music promotion platform focused on Spotify playlist pitching. Depending on who you ask, it’s either the most popular or second-most popular firm in the space. Don’t ask me. I’m an innocent bystander.)

You can read my whole review if you want. But the short version of it is that I ran a campaign for one of my brother’s tracks and got about 40,000 solid Spotify streams, plus continuing algorithmic growth.

I thought that was pretty good, so I conditionally recommended the service.

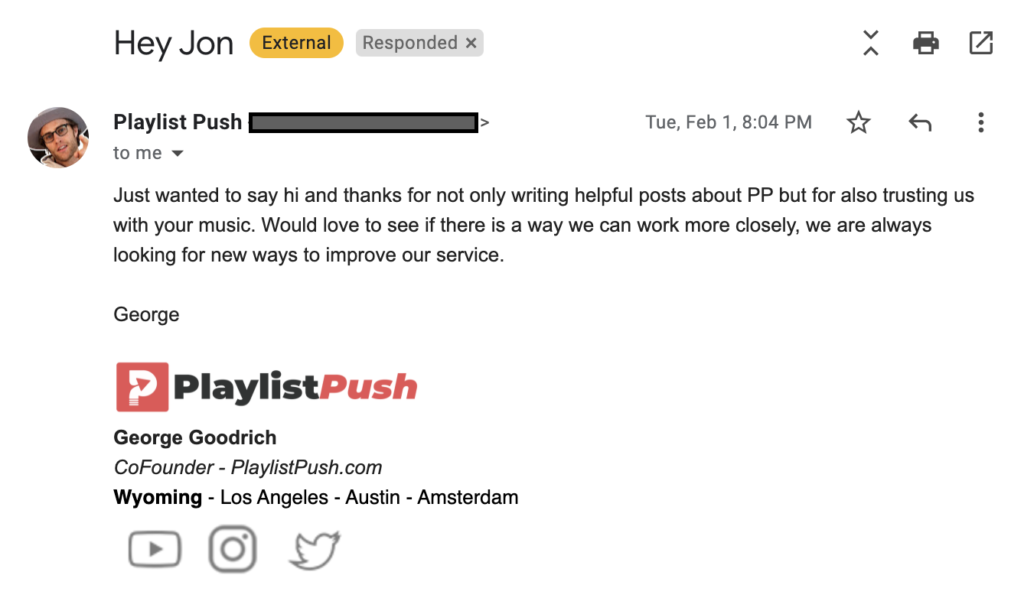

George Goodrich noticed.

George is the founder of Playlist Push. Prior to last month, I’d known who he was because I’d read Ari Herstand’s review of the service (he mentions getting lunch with George) and because George is the face of Playlist Push’s YouTube channel.

But I hadn’t had any personal contact with George until he sent me this email:

Tbh I thought his little profile photo was kinda weird, but I appreciated the email – and as I mentioned last week, I’m all about connecting with playlist pitching companies (really, with anyone in the music marketing space).

So after a little back-and-forth, we set up a time to talk. It turned out to be a really enjoyable conversation.

Here are a few takeaways from it.

1. George is a real interesting dude.

I started off by asking George about his background. George responded by talking about Tai Lopez.

Didn’t see that one coming.

Tai Lopez is, according to the internet, an “internet personality investor entrepreneur,” which is a jargonized way of saying that a lot of people would really enjoy hitting him with a water balloon.

But, when George met Tai almost a decade ago, Tai wasn’t yet the cringey “I’m here in my garage with my Lamborghinis” guy – he was just an up-and-coming entrepreneur known for networking in the LA social scene.

“Look, I know people have a lot of opinions about Tai,” says George. “I totally get that. But about a decade ago, he was just having these get-togethers at his house.”

“I was at UCLA at the time, working at a country club, and I’d go over and meet a ton of interesting people,” he continues. “And talking with some of them, I realized that I needed to make a drastic change.”

So, George applied for a travel visa to western Australia.

His plan, as he put it, was to “get some real experience in the music industry, then come back to the US and get a job using country club contacts.”

It mostly worked, but it wasn’t a straightforward path.

George spent a few years in Australia working as an event promoter. He did Australian things: He surfed, worked at a brewery, and presumably said things like “G-day!” and “Pass the tinny!”.

He also did music-industry things: He put on a ton of shows, he connected with a bunch of DJs, and he worked with Flume’s manager. It was good experience. Eventually, he felt like it was time for him to come home, so he headed back to the US.

But before coming all the way back, he stopped in Amsterdam to visit a friend. That random decision had big consequences: It was there that he met a developer named Ludo, who’d become his friend and business partner.

Together, they founded a company called Demo Drop.

Demo Drop was a platform for DJs to upload demos. Martin Garrix may have been discovered on it. It closed last year. Idk much else about it; here’s the link to the last post from Ludo.

From there, George made it back to the States. He ended up getting a job at Repost Network, a company that offered a SoundCloud monetization service and has since been folded into SoundCloud itself.

The job didn’t last very long, but it gave him valuable experience; as he was working with SoundCloud artists, he realized that a bunch of artists were blowing up through placements in third-party playlists. So, after parting ways with Repost, he wrote an e-book about getting on Spotify playlists (you can still find it online), and soon found that there was demand for a service to help.

So he called up Ludo.

“I told Ludo that we should take a look at Spotify playlisting, because there was a ton of hype around it that wasn’t very transparent,” George explains. “I thought we could make it more cost-efficient and clearer.”

George got in touch with nine playlist curators that he knew personally, and he and Ludo quickly put together the first version of Playlist Push.

The model was this: Artists would pay $40, and their song would be sent to all 9 curators.

Using a simple interface, curators were paid to review submitted tracks and give feedback. Sometimes, tracks would get placed. Placements led to streams. Artists could see everything that happened: feedback, placements, rejections.

That was in 2017. Things grew rapidly from there.

2. For playlisting companies, volume and screening are how you win.

It wasn’t long before Playlist Push started getting serious traction.

“People were seeing results with it,” says George, “so they started sharing it with each other.”

And George and Ludo kept pushing the platform forward, too. They quickly realized that adding curators would be key to growing the service. So, in the early days, George scoured Spotify to find good lists, then asked if their owners would want to join up.

“I’d literally just search keywords on Spotify and see who was popping up,” George recounts. “Most accounts at that time were tied into Facebook, so we’d message people to ask if they wanted to join.”

It wasn’t a very difficult sell; the pitch to join the platform is basically, “Hey, do you want to get paid for something you’re already doing?” George estimates that 80% of curators he contacted said yes.

Things snowballed quickly. It wasn’t long before curators were actively reaching out to Playlist Push, genre buckets started being created, and George stopped manually recruiting. The influx brought benefits and challenges.

As I’ve written before, maintaining a strong curator network is the foundation of any playlist pitching service.

The more curators you have, the more opportunities artists have to get placed. This tends to lead to better results.

But the more curators you have, the more difficult your network is to manage, because curators are constantly creating new playlists and cutting old ones.

Plus, engagement on playlists rises and falls over time. For example, listeners aren’t going to stream “Indie Winter 2020” in the summer of 2021, or the soundtrack to Dunkirk five years after the movie is out.

The bottom line is that each playlist has a unique lifecycle, which is why George (unsurprisingly) doesn’t buy the idea that “all third-party curated lists are filled with bots.” The truth is that every playlist is unique – but that means screening processes are critical.

According to George, there are two methods Playlist Push uses to screen lists.

First, there’s an automated process. Curators submit the list to the platform, and Ludo’s set it up so that followers and listeners are automatically pulled in. This data is analyzed via algorithm to make sure there’s real engagement.

But, second, there’s still a manual process. George told me that the team at Playlist Push actually listens to every playlist that’s submitted, because, as George bluntly puts it, “Sometimes people build a list and then just start sneaking trash in there to make money.”

To keep trash out, there’s also a regular monitoring and auditing process.

FREE RESOURCE 👇

How to spot fake playlists

These four signs show that a playlist is built with bots – before you’re placed on it.

Get the guide to stay safe, avoid scams, and go after real streams.

The results have been pretty solid, both in terms of volume and in terms of list cleanliness; check out the site, and you’ll see that they boast around 1,000 curators.

And George tells me that, after promoting thousands of artists, they’ve only ever had one song flagged by Spotify – and when the artist reached out to Spotify noting that they’d only promoted through Playlist Push, the song was immediately cleared.

But I think the clearest sign that Playlist Push uses clear lists is in the after-campaign results.

Because here’s the not-that-fun truth:

3. Spotify promotion is a long-term game.

A common scenario when running a playlist pitching campaign is that streams spike while the song is on playlists, but when the song gets taken off, things crash back down to previous levels.

If the placements weren’t relevant or if listeners were disengaged / bots, this kind of activity can be really harmful for artists.

Basically, Spotify is seeing that a song was put in front of a bunch of people and none of them liked the song enough to engage with it (by favoriting it, clicking to the artist profile, adding it to their own playlists, tattooing it on their calves, whatever). As a result, Spotify won’t show the song to other listeners, because in the algorithm’s eyes, it’s a dud.

Spotify is dud-averse – they want to keep people listening.

So, in this scenario, the next time the artist releases a song, Spotify’s algorithm will dampen its reach. For the artist, this is obviously depressing.

But there’s a flip side to this.

When you run a good playlisting campaign, you get put on playlists that have active listeners who engage with your music.

This lets Spotify collect more data on your song – they can see what kind of users like it and what kinds of artists you’re similar to. With this kind of encouragement, the algorithm can do its thing and put you in front of the listeners who will like you.

It’s a cycle; the more data Spotify has, the more inclined the platform is to place you on Radio or Discover Weekly or Daily Mix. And the more you’re placed, the more data Spotify has, so the more likely they are to place you.

Each time you release a song, you stair-step up the ramp of engagement.

I saw this when I ran my Playlist Push campaign for Tom’s song – after it got taken off of the playlists, its baseline level settled at about 300 streams per day higher than it had been before the campaign.

As with getting press placements, this is the process of rolling a snowball. And it takes time.

The bad news is that you almost definitely aren’t going to blow up with one release.

George mentioned that the artists that have regularly invested with Playlist Push have seen the best results. He name-dropped a rapper who’s put out a song every week or two for a few years (which is insane). Most of those songs have run through Playlist Push campaigns, and last month, the artist passed 2.5M monthly listeners on Spotify.

That’s how you win the game: You play it consistently over the long-term.

That’s what George and the team at Playlist Push are doing now.

“When you just try to go for the money fast, you burn people,” says George. “The pool dries up quickly.”

He’s focused on avoiding that, which means constant combing through curator playlists, proactive (now mostly automated) communication with artists, and a bunch of customer service (with a team he and Ludo have built up).

Honestly, I don’t envy him the job. I think running a playlisting company sounds really hard.

But I also think, if it’s done right, it’s a really valuable service for artists.

As I stated in my review, I don’t unconditionally recommend Playlist Push. Results are never guaranteed, curator networks are always changing, and there are plenty of artists who’d be better served by focusing efforts elsewhere.

But I do think George has built a legitimate service that’s really helpful for a lot of artists. That’s true even though he knows Tai Lopez and his little email picture is kind of weird.

Playlist Push is a cool platform. Here’s hoping the pool stays filled.