I watch YouTube videos now.

Before last year, believe it or not, I rarely watched YouTube videos – like, almost never. But last year I started my own channel, and since then I’ve been on the platform much more often.

I’ve consequently discovered how hard it is not to click a thumbnail that piques your interest. And also how much time you can waste hovering over thumbnails, trying to evaluate videos by reading the (very small) closed captions as they autoplay.

I love and hate the internet.

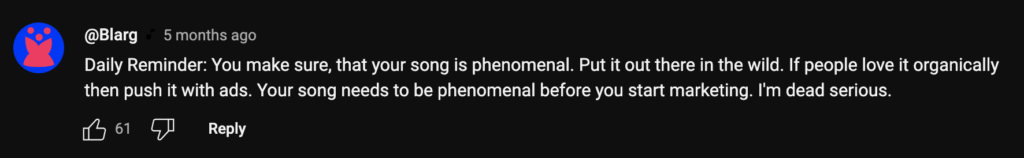

Anyway, my dumb social media habits are neither here nor there. My point in telling you all this is just to share that I came across the following comment under an Andrew Southworth video and found it interesting:

“Interesting take, Blarg,” I thought. Then I spent longer than I’d like to admit formulating a response in my head.

Forty-seven-ish minutes later, I determined that my words would be wasted in a YouTube reply and that it’d be more worthwhile to share them with you.

So here you go.

I think Blarg is kind of right.

The core factor in whether or not music marketing works is the quality of the music.

If the music is good, marketing takes on a natural momentum. If the music isn’t good, marketing is a grind, like pushing a boulder up a hill.

There’s nuance to this, of course; a song’s quality isn’t the only factor in its potential success. A great song in a niche genre, for instance, is harder to market than a great song in a mainstream genre. Like, no matter how good your avante-garde jazz song is, the very fact that it’s avante-garde jazz will make it a more difficult song for which to find an audience.

But, in general, Blarg’s got this bit right. The quality of the music is the foundational factor in whether you can get marketing traction with it.

Rabbit trail in small font that you should skip if you don’t want to get distracted: Yes, I think the quality of music, and of art in general, is an objective reality. My perspective is that there are two primary factors in determining whether a song is “good”: 1) The purpose of the song, and 2) how well the song achieves its purpose. Different purposes allow capacity for greater or lesser degrees of goodness. For instance, a song whose purpose is to soundtrack an insurance commercial has less capacity for goodness than a song whose purpose is to communicate a deep feeling of joy. But a song has to fulfill its purposes to be good, too; a song that perfectly soundtracks an insurance commercial is better than a song with poor production and lazy lyrics that utterly fails at communicating deep joy. The best songs are those which both pursue the highest purposes and most successfully fulfill them. Finally, I think that, while there is objective goodness to art, it’s incredibly difficult to actually measure what good is (who can say which purposes are really better, or which song more truly achieves its goals?), and as a result it’s probably not worth talking about. Having wasted two minutes of your life, let’s get back to the main thread.

I also think Blarg is kind of wrong.

I have two points of contention.

First, I don’t agree that the way to evaluate whether a song is worth marketing is simply to, as Blarg says, “put it out there in the wild.”

In fairness to Blarg, who has left us only a five-sentence YouTube comment, I may be making an incorrect assumption as to what “the wild” refers – but I take it to mean basic distribution and organic social media posting. Given that assumption, here’s my beef: Just because you distribute and post about your song organically, there is absolutely no guarantee that anyone (and especially the right people) will hear it.

I mean, sure, if you already have 10,000 followers on Spotify or Instagram, that’s one thing; you’ll be able to measure the level of engagement of your existing audience and use that as a barometer for the song’s greater potential.

But if you’re starting from near-zero with your audience (or, really, anything under a few thousand followers), then distribution and organic social alone won’t get the job done. You could release “Stairway to Heaven” and it’d be a tree falling in the forest – nobody would hear it, no matter how good it happened to be.

Second (and relatedly), I don’t quite agree with the idea that “your song needs to be phenomenal before you start marketing.”

As I’ve written above, I do think that the quality of a song undeniably impacts how effective marketing can be. But I also think that running paid ads can actually help you to evaluate the quality of a song.

Let’s say you run some Facebook ads and see low costs-per-results to Spotify streams, plus a ton of positive feedback; that data suggests that the song is good and worthy of more spend.

And paid ads can also help you to find the right people – the ones who will like the music you’re making. Starting from near-zero and expecting to find your ideal audience simply by releasing your music into the world is a little naive.

So there, Blarg.

Okay, so when should you spend money to market your music?

If you’re tracking with me so far, this is probably your natural follow-up question. The answer, as always, is that it depends (sorry). But here are a few thoughts.

1. You should only pay money to market music that you think is good.

“Wait, wait, wait,” you protest. “Didn’t you just drag poor Blarg through the dirt for daring to suggest this same idea?”

No. For one thing, I did not drag Blarg through the dirt – I presented my disagreements in a well-meaning, mostly-respectful manner, okay? Geez.

And for another thing, I’m saying something fundamentally different from Blarg: You do not have to know that a song is phenomenal in order to spend money on it – you only need to have a hunch for the spend to be worth it.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we usually feel it when our songs fall significantly short of the ideal. I think this is a natural part of being an artist. Conversely, most of us have a hunch, deep down, when we’ve made a song that’s really, legitimately, actually quite good.

Spend on the ones you have the good feelings about.

And if none of that resonated and you just aren’t sure if your song is any good, here are two tactics to help you evaluate it:

Make a playlist of five reference tracks that have inspired your song (preferably by artists you love). Add your song to the playlist and listen to it on shuffle. When your song comes on, does it feel out of place in terms of production level, or performance value, or songwriting quality? If it does, don’t pay to promote it.

Ask five friends for honest feedback. Tell them that you’re considering spending money advertising this track, and that you’d prefer they spare your wallet rather than your feelings.

2. You should pay money if you want to reach new ears.

There’s some gray area here, but generally, if you’re satisfied with the audience you already have, then you don’t need to spend as much money on marketing your music.

It’s totally possible to build a fanbase of, say, 1,000 diehards and be content at that. If this is the case, then email your list, post organically, and put your music out; you don’t need to spend all that much.

Of course, most musicians (like most people) struggle to be content with what they have. My guess is that you and I fall into this boat.

If you’re looking to grow your audience, then the cold reality is that spending money will make it happen much faster.

The bottom line is this:

1) You should have a clear goal with any spend you lay out, and 2) you should have a hunch that your music is worth spending money on.

If you can meet both of those requirements (and you also have money to spend) then spending is probably worth it.

And again, my guy Blarg is right: Above all else, you should primarily be committed to making great music. Excellent music not only makes marketing easier – it’s meaningful in itself.

That’s all I’ve got for today; I’m off to find more YouTube commenters to disagree with. (It’s not hard, but it does take several hours.)

As always, here’s wishing you good luck.